John Pollack

A former speechwriter for President Bill Clinton, John Pollack has built the world's first cork boat.

Prior to his work in the private sector, John worked at the White House and on Capitol Hill, where he was the wordsmith for House Democratic Whip David Bonior. John's speechwriting skills developed from extensive campaign experience and his work as a journalist, both in the United States and abroad.

A 1988 graduate of Stanford University, he began his writing career as a reporter for the Hartford Courant, covering local government in suburban Connecticut. Later, he spent three years in Spain as a foreign correspondent, covering everything from business to bullfights for the Associated Press, the Los Angeles Times, Advertising Age and other media. His first book, The World On a String: How to Become a Freelance Foreign Correspondent, grew out of that experience. Recently, he published Cork Boat, a non-fiction account of his 30-year quest to build a 22-foot Viking ship made completely from wine corks, and its 2002 voyage down Portugal's Douro River.

To the chagrin of his colleagues, John won the 1995 World Pun Championship - his first and only world title. He lives in New York City.

JP: Is it registering?

DR: Yes it is…

JP: Test one, two…

DR: Testing, testing…

…So start by telling me about your life.

JP: Well, I think that everyone starts out creative and that society trains people to be specialized and sometimes people become creative in very specialized ways. Most people, beyond a certain age, are discouraged from being creative.

…I'm not an artist but I would say I am creative and that creativity takes different forms.

I am probably best at writing because that's what I do for a living.

When I built The Cork Boat, which I had envisioned when I was…six years old, people said…"How do you know how to build a boat?" And I said, "I figured it out." I had some limited experience. I'd sailed and I enjoy boats so, I understood things. But I think that anybody could have built The Cork Boat if they had set their mind to it. And I just happened to decide that's what I wanted to do and nothing was going to stop me.

DR: And you decided this at six years old?

JP: I did. I built a boat that sank -- out of old crates and firewood - and I brought all the neighbors to the launch. I invited all the neighbors to the launch at the pond at the end of our block. I stepped aboard the boat and then, promptly it sank to the bottom. Of course it was only about a foot and a half deep…But I wasn't discouraged! I thought "Wow! I built a real boat!" And that's when:

"I just have to build out something guaranteed to float."

So I started thinking about what I could build the boat out of and I ultimately realized that -- you couldn't sink a cork. So then how could you sink a cork boat?

So I would start saving corks. I asked my parents to start saving their corks. And being parents who encouraged creativity, they said "Great!" But I didn't realize they were only drinking one or two bottles a week and I was growing faster than that. I outpaced their uh, cork production

DR: (Laughing) Consumption.

JP: (Laughing) Yeah. For many years.

DR: How do you deal with challenges? I gather by what you were just saying that you used the boat sinking incident when you were six as an opportunity to figure out how to do it successfully.

JP: Right. And it took a lot of trial and error. When I revived the project…it became a running joke in our family. When another cork would go into the wooden bowl in the kitchen, "Another cork for the boat!", and "When are you going to build that boat?" I'd say "Don't worry. Keep drinking."

Then at thirty, I guess I was thirty three and working in Washington and a little discouraged with some of the…It was post impeachment and it was a little bit…it was a cynical time. I decided I needed to take a creative sabbatical, get out of it -- the trench warfare, and see what I could achieve if I applied my creative energies toward an endeavor which nobody was trying to stop.

In D.C. there is something that is called "the culture of creative destruction", where you have all these smart people, even some smart Republicans, trying to…you know pouring all their creative energies into stopping the other guy. Sometimes the other guy needs to be stopped, but it becomes akin to World War I - fighting over the same hundred yards of muddy ground, over and over and over. I decided to step away from that, take a creative sabbatical, write, build a boat and see what I could accomplish if no one were trying to stop me.

DR: And was there anything more in particular that you were trying to accomplish or demonstrate in building the boat…

JP: The power of WHIMSY. I think whimsy is really important in this world, especially because we live in this "bottom line" society where everything is measured in dollars, celebrity and material gain - consumption. The Cork Boat was about none of those. It was about fun and playfulness and possibility and whimsy.

DR: And I imagine that people did have fun participating with you?

JP: Yeah, some did. Some did. I was constantly recruiting because it was very labor intensive. There was a certain Tom Sawyer-esque quality to the project, not just because of the boat and the trip to come, but there was a lot of drudgery, potential drudgery. We had to sort out a third of a million corks by hand.

First we had to collect the corks and then sort them by hand because not all corks are created equal. And we needed the ones that were not the bits and pieces glued together, or not the plastic ones but the good pure corks. They're more buoyant and don't absorb water. And then we had to assemble them all.

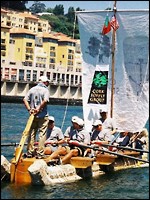

The Cork Boat was assembled from 165,321 corks and there's not a drop of glue connecting them. They are held together with 15,000 rubber bands, commercial fishnet and Dacron line. And so the assembly of these corks into a very organized repetitive pattern was incredibly labor intensive and it took a lot of people. But it was a social endeavor and I was constantly recruiting at parties.

I'd go to parties and people would say "What do you do?" And in Washington they expect you to say "Oh I work for Congressman so and so, or "I'm an expert on such and such." And I'd say "I'm building the world's first cork boat. What are you doing on Saturday afternoon?" And they'd say "What? What are you talking about?" And then I would explain the project and try and get them out there.

I'd make up a couple jugs of lemonade and it was very social and a whole community, a small community grew up around the boat, as people became regulars. We just became obsessed with this project. And I think one of the attractions of The Cork Boat in Washington was that there wasn't a cause associated with it except, whimsy. In everything there's always an agenda in Washington and people asked questions trying to figure out what the angle was and there was no angle. There was a certain joy to that…that attracted people.

DR: So talk to me about what inspires you.

JP: What inspires me in general?

DR: Yeah.

JP: Details inspire me. Good design inspires me. Word play inspires me. Visual puns inspire me….I think people who are really good at something inspire me - the more obscure the better.

DR: And what are you really good at?

JP: I am good at writing. I am good at English language. If you look at people who are really good at something, it's usually because they love it. And I just think English is so much fun because it's so malleable and you can play with it and it has endless combinations and possibilities and it's just really fun to see where it can take you.

People say "What's the connection between your writing and The Cork Boat?", or "What's the connection between speech writing and The Cork Boat?"

Speech writing for Clinton is obviously a conventional success and I loved it. It was a great…I mean I set out to do that and I was thrilled for the opportunity to do that. By the way, I was rejected four or five times by the White House before I got in there.

DR: So I am putting the pause button on. I am going to come back to that….

JP: And I say that it's all about assembling small pieces into a…you know marshalling all of these small pieces around an idea to create this coherent whole that is greater than the sum of it's parts. So a speech…starts out as all these…you have a million words in the English language and you marshal them around an idea and organize them to create something that…to create a talk…that will carry people somewhere. The Cork Boat was, in some ways, very similar, in that you take all of these individual pieces that, by themselves don't tell a story, but you marshal them around an idea -- in this case a boat. And then the boat carries you some place. It's that assembling of small pieces that I find very interesting.

I think that's the way life is. You assemble small moments that tell a story ultimately. I think a lot of people spend a lot of time looking for a narrative in their life, 'cause everyone wants to find meaning. Sometimes we veer off and we don't know where the story is going, but it's just like building a cork boat. If you focus on the small pieces and around some general principle or some general direction, you get there -- ultimately.

DR: Tell me something that you discovered about yourself while building…

JP: …The Cork Boat?

DR: Yeah.

JP: That I'm a stubborn son-of-a-bitch. Which, I think I knew but, I worked with a partner on this project - my friend Garth Goldstein, G-A-R-T-H, G-O-L-D-S-T-E-I-N. Garth was just as stubborn as I was.

I learned that you can have intense conflict with someone that you are close to and that does not destroy the relationship; that in some ways, it makes it more real and makes it stronger. That's probably the biggest lesson that I learned -- that friendships endure conflict. I think that we're both somewhat conflict averse and not addressing these conflicts as they came up, they tended to build up into fire balls…I learned to address these things one by one rather than letting them build up into bigger conflicts.

DR: Is there anything that you discovered about people; human nature?

JP: I don't know if this was a discovery but it was another example; it helped me articulate something I've seen in political campaigns:

The Cork Boat was this expression of possibility and hope and fun and whimsy that no one of us could achieve on our own, but together, we could create something. And I invited everyone who participated to come to Portugal when we took it on our trip there. And a couple people did, and a lot of people shared it vicariously.

DR: So now I am going to take the pause button off and go back to the four rejections. What was that like?

JP: Well I worked in politics - on campaigns, and I had worked as a journalist, as a reporter. I had left journalism and I…was living in Ann Arbor at the time -- and I was trying to decide…I needed to move to a bigger city. I was, I don't know, early thirties. It was either Chicago, New York or D.C. Chicago was the dark horse, Mid-western candidate. New York was too intimidating - very attractive but too intimidating, and D.C. I thought, "I could probably get the best job in D.C. I know what that's about." So I decided that I would just move to D.C. and see what I could find.

I used to work at the Henry Ford museum…outside of Detroit…and I stopped in the cafeteria to say goodbye to some people and a friend said "Oh, are you looking for contacts in D.C.? and I said "Yes." And she said "Well my old college roommate is Hillary's chief speech writer. Do you wanna talk to her?" And it was like this light bulb went off in my head. I thought "I could be a speech writer. I know politics. I know how to write. How hard can speech writing be?" So I went to Washington and started pitching myself as a speech writer.

This was the beginning of Clinton's second term and people would say "Well you've never written any speeches before." And I said "Well I know politics. I know how to write, give me a speech and I'll write it for you." And, lo and behold, I could write speeches.

I got a job on The Hill, in The House, writing for David Bonior, who was a Congressman from Michigan and the Democratic Whip - number two Democrat in The House and that was trial by fire because he spoke many times a day. Sometimes to five hundred people in a room, sometimes on the floor in The House - small fundraisers - all different formats and audiences and I was his only speech writer, so it was nose to the grind stone. I learned a lot.

In my interview at the White House, when I spoke to Hillary's speech writer, I met one of her staffers. We struck up a friendship and she would keep me informed when an opening would come up at the White House. Each time I applied, I would get a little bit closer, make a few more contacts, I would have gotten more experience, would do better on the writing test….

….And, let's see…I'm trying to think. I was rejected by the First Lady's office. I was rejected by Gore - thank goodness. I was rejected by the National Security Council. Rejected. I think I got in on my fourth try. No fifth try.

DR: So you had no doubt decided that this was something…

JP: Yeah, I wanted to be…

DR: …that you wanted to do…

JP: …as early as I can remember reading the paper, the people that I was most impressed…and this seems apocryphal but it's funny how these things come to mean something later…

DR: (whispering) Spell apocryphal.

JP: A-P-O-C-R-Y-P-H-A-L. But you better spell check it. I always admired the Presidential speech writers. I thought that they were cool. And I never envisioned that I would ever be one. But then once, when I moved to D.C. and decided to become a speech writer, I thought "Well, if I 'm going to be in speech writing I might as well be a Presidential speech writer." And Clinton was such a great speaker, to be a speech writer for him was a great joy. And then ultimately on my fifth try, I was hired.

But I'll tell you The Cork Boat connection.

DR: You read my mind.

JP: I had left The Hill in 2000 to be captain of my own ship. I said "I'm going to take this creative sabbatical." which I had mentioned. I was going to start off the new century with a creative sabbatical. I was growing discouraged because The Cork Boat…I was having some arguments with Garth and collecting the corks was difficult and it wasn't so easy to figure it out and I got a call from the White House one day saying that there was a position open and, would I be interested in interviewing, could I come in that afternoon? And there I was sitting in my shorts and t-shirt and unshaven and I said "How about tomorrow morning?" They said "Fine. Send in your new resume"…So I updated my resume and I added on the last line under "Other":

Currently building the world's first cork boat.

I figured "What the hell. That's what I'm doing right now."

DR: Yeah, yeah…

JP: So I go in there and I sit down with Terry Edmonds, {the Presidents head speech writer}. He's sitting behind his desk and I am in the basement of the West Wing and I am nervous because this is my best shot; this is the last shot that I have because the administration is in its final year and this is it! If I don't get this, I'm cooked.

And he was looking through my resume and he kind of pushes his glasses to the top of his head and he says "I have no doubt about your writing capacity, but I …you seem to have a lot of other…" He starts to struggle to find the right word…Oh no! If the head speech writer for the President of the United States is struggling to find a word, I'm in trouble. He says "You seem to have a lot of projects going on. You know this is a very demanding world that you are being considered for. What's this cork boat?"

And I told him that The Cork Boat was…I had to think fast…I told him that The Cork Boat was, what it was and how it was an expression of creativity and that creativity was fundamental to speech writing, and it was the assembling of small pieces into the more coherent whole and of course I would put it all on hold for this opportunity, were I so fortunate as to be selected as a Presidential speech writer.

In the end I did get the job and I got the White House saving corks for the boat. And so that's how The Cork Boat came into play in the whole White House hiring.

DR: Talk to me about what you are most afraid of.

JP: I would say that there are two things. One is being ordinary and two is being lonely. But I am very fortunate in my current life, in that, through this coffee shop, Jack's, I have made very, very…I make good friends and I keep my friends. But we live in a world where people are scattered. You can have a great friend in Chicago and you can talk to them on the phone and that's great but they're in Chicago. But here at Jack's ….there's Larry and Jack and Tom Roth and we've just got this great core of friends …and as someone who works independently, having that social network right next door is priceless. So, that kind of helps address…

Cork Boat : A True Story of the Unlikeliest Boat Ever Built

Amazon.com

Most people have childhood dreams; few ever pursue them. At the age of 34, John Pollack quit a prestigious speechwriting job on Capitol Hill to pursue an idea he had harbored since the age of six: to build a boat out of wine corks and take it on an epic journey.

In Cork Boat, Pollack tells the charming and uplifting story of this unlikely adventure. Overcoming one obstacle after another, he convinces skeptical bartenders to save corks, corrals a brilliant but disorganized partner, and cajoles more than a hundred volunteers to help build the boat, many until their fingers bleed. Hired as a speechwriter for President Clinton midway through construction, Pollack soon has the White House saving corks, too. Ultimately, he and his crew set sail down the Douro River in Portugal, where the boat becomes a national sensation. Written with unusual grace and disarming humor, Cork Boat is a buoyant tale of camaraderie, determination, and the power of imagination. Purchase John's book on Amazon:

[»] Cork Boat : A True Story of the Unlikeliest Boat Ever Built

DR: …the fear…

JP: … that issue.

DR: Yeah.

JP: And then on the being ordinary front, I have gotten better as I've gotten older at recognizing that you can't be on top of Mt. Everest everyday. There's a lot of slogging through the valleys. So if you've got a cork boat or a job at the White House…there's going to be a lot of slogging between those peaks and you have to be patient. And I am much more patient and more forgiving of self then I used to be. When I make my New Year's resolutions…one of the standing resolutions each year is to be more forgiving of others and myself.

DR: And how's that goin'?

JP: I'm making progress. I'm making progress.

DR: Tell me John, a hundred years from now what do you want to be remembered for?

JP: Well "A", I don't think that I'll be remembered a hundred years from now, BUT -

I didn't set out to write a book about The Cork Boat but when I came back…people had said "Oh are you going to write a book?" and I said "Well if we go on a trip maybe I'll get a book out of it." And the journey was so incredible that I realized that if I didn't write it down, that a couple years from now I'd remember a few of the stories and then ten years, fifteen years down the line, it would be a warm memory...and what I was feeling is that, that incredible story would have disappeared entirely except for a couple of photographs.

Then I said "I have to write this down." And I wrote the story and now that it's a book, I know that maybe a hundred years from now it will be some rainy afternoon and somebody will be a little bit bored, maybe, and they will be looking at the bookshelf and they'll say "What's this book?" And they'll pull the book Cork Boat off the shelf. They'll sit down to read it and they'll think "Wow this is an incredible story!" And the story of The Cork Boat and what it symbolizes and the lessons that it carries, will live on. And I think that, the story will live on, matters.

DR: Anything else?

JP: Well I suppose that a hundred years from now it is entirely possible that I will have grandchildren - alive, and they will have fond memories of their grandfather…

Thanks John!

The Pun Also Rises: How the Humble Pun Revolutionized Language, Changed History, and Made Wordplay More Than Some Antics

Amazon.com:

A former word pun champion's funny, erudite, and provocative exploration of puns, the people who make them, and this derided wordplay's remarkable impact on history.

The pun is commonly dismissed as the lowest form of wit, and punsters are often unpopular for their obsessive wordplay. But such attitudes are relatively recent developments. In The Pun Also Rises, John Pollack-a former World Pun Champion and presidential speechwriter for Bill Clinton-explains why such wordplay is significant: It both revolutionized language and played a pivotal role in making the modern world possible. Skillfully weaving together stories and evidence from history, brain science, pop culture, literature, anthropology, and humor, The Pun Also Rises is an authoritative yet playful exploration of a practice that is common, in one form or another, to virtually every language on earth.

At once entertaining and educational, this engaging book answers fundamental questions: Just what is a pun, and why do people make them? How did punning impact the development of human language, and how did that drive creativity and progress? And why, after centuries of decline, does the pun still matter?