Pulitzer Prize Winning Photojournalist, David Turnley

David Turnley is considered by many to be one of the best documentary photographers working today. He won the 1990 Pulitzer Prize for Photography, and has been a Pulitzer Prize finalist four times. In 1988 and 1991 he won the World Press Picture of the Year.

Turnley was a Detroit Free Press staff photographer from 1980 to 1998. He was based in South Africa from 1985 to 1987, where he documented the country under Apartheid rule. He was based in Paris from 1987 to 1997, covering such events as the Persian Gulf War, revolutions in Eastern Europe, student uprisings in China and the disintegration of the Soviet Union.

Turnley earned a B.A. in French Literature from the University of Michigan, received an Honorary Doctoral degree from the New School of Social Research in 1997, and has also studied at the Sorbonne in Paris. He studied under a Nieman Foundation Fellowship at Harvard in 1997-1998.

In 1998 David began working in video as well as still photography. He incorporated the two in a documentary The Dalai Lama: At Home in Exile (CNN), which was nominated for an Emmy. He has since had four pieces featuring a similar topic shown on ABC's Nightline. In 1999, he produced, directed, and photographed his first feature-length documentary, La Tropical, a sensual portrait of a wildly popular dance hall in Havana which has been central to the lives of working-class Cubans of color for more than half a century. La Tropical recently won Best Documentary in the Miami International Film Festival, and the film is currently being seen in festivals around the world.

David is the author of Baghdad Blues: A War Diary and the co-author of David & Peter Turnley: In Times of War and Peace.

To be with David Turnley is to be in the presence of your own magnificence because he has an unusual ability to see people beyond the accepted conventions; to capture the humanity that lies just beneath the surface. It is my pleasure to know him. Enjoy what he has to share about his work, his point of view and about his new book.

DR: I have to say that I envy, in a lot of ways, the kind of life that you have lived as a result of the work that you do.

DT: I was only seventeen when I started photographing.

When I finished college I had such a drive to photograph because I enjoyed it and I was at a place in my life where I had no other responsibilities. The only thing I had to do was figure out how to pay rent. I lived in a room in Ann Arbor, Michigan for about three years and I started working at these small weekly newspapers, paying $75 a month for this room, making twelve to thirteen thousand dollars a year.

My job was to go and tell stories and I had a ball!

My next job was at The Detroit Free Press and I had to find a place to live in Detroit. I found a beautiful apartment in the only integrated part of town and because it was in the city at a time when Detroit, after the riots in '67, this was now in the early '80's, had become essentially about 95 percent Black because there had been this White flight to the suburbs. This one integrated neighborhood wasn't particularly sought after so I rented a nice apartment for about $300 a month. My point is that I had no other responsibilities to anything but myself...

DR: What a luxury...

DT: That was the way I lived my life for a really long time. Things started to get a little more complicated when I got married and had a child and had to take on more practical realities.

DR: Tell me about the book that you have recently finished; the Nelson Mandela book.

DT: The first time I heard the word apartheid was when I was thirteen and my father had come home from work one evening. We were at the dinner table and he was so upset because -

"The Rotary Club had invited two pro-apartheid South African speakers to speak at our meeting today and I stood outside with a placard that said 'Down with the apartheid regime in South Africa!'".

He told me that the most depressing thing was that none of the Rotarians walking into the meeting knew what apartheid meant. Then I said -

"Dad, what does Apartheid mean"?

He explained by telling me about this man named Nelson Mandela who was in prison fighting to change the status quo.

That was my first awareness of the idea that apartheid was this racially legislated system that preserved all power of being a citizen to the minority population that was White, that was at the time 7 million, versus a majority population of 38 million people of color. As much as I knew it to be shocking, the realities that I grew up with in Fort Wayne, Indiana were not that different.

There wasn't a racially legislated system where I grew up but the inner-city was Black and the periphery was White. The inner-city was poor and everything else was middle to upper class. I experienced a profound sense of division within his society.

It occurred to me that to go to South Africa to photograph would be an opportunity in some sense to look at the tragedy of the racial prejudice that I had experienced in my own country in a way that might make more sense.

I was able to get The Detroit Free Press to send me to South Africa to work with a correspondent that they had based in South Africa already, to complete what was meant to be a six week assignment looking at, not so much what apartheid was, but how it manifests in a day-to-day way...

DR: When was this...What year was this?

DT: I first went to South Africa in 1985 and it was really still in the midst of apartheid being absolutely the status quo. But it was also during the time when the society was a powder keg about to explode.

Mandela at that point had been in prison since 1964 and it was at a time when the rest of the world was imposing sanctions against South Africa. America had really resisted imposing sanctions. It's ironic because the administration at the time argued that it was better for America to conduct what they called constructive engagement, which meant that if they actually stayed engaged with the South African government they had a better opportunity to help influence the direction of the country, as opposed to cutting themselves off and creating sanctions. I say that it is ironic because it is exactly the opposite of how we've conducted a policy towards Cuba.

Never-the-less...

I went to South Africa in '85 for what was supposed to be a six month assignment and literally the day I arrived, the then president Pieter Willem Botha was, in a speech to the country, wagging his finger. It was a speech where people expected that their government might actually lessen the grip of apartheid and start to head toward changes and improvement and in fact -- he wagged his finger at the camera and said that South Africa would not be influenced by foreign governments.

DR: Feels a little familiar...

DT: As that happened, which was literally the day that I arrived, the townships in South Africa just sort of blew up.

That began my coverage.

Within the first weeks of my stay I was in a different township up and down the country everyday photographing confrontation between Blacks in townships and the police and military. It was a fortuitous time for me, as a photojournalist, to be there. The government had just stopped giving visas to other foreign photographers. I was one of the last to get a visa to get in. So, not only was my work going to The Detroit Free Press but it was being published in magazines all over the world because I became one of the few sources of images that were depicting what was happening on a day to day basis.

It was such an aspirational time although it was tragic to witness these confrontations. Inevitably in all of them there would be one if not many people killed, and then there would be subsequent funerals every Saturday. Because the government prohibited any political activity, funerals became the only place where Blacks could congregate to manifest a political solidarity. These were the events where Arch Bishop Tutu and many other activists who were forced to work underground would be able to come and speak to large audiences.

The first period of my work in South Africa for the first six months was spent photographing the unraveling of this powder keg that was exploding. The government imposed a state of emergency which tried to suppress all political activity for the next two or three years but it became obvious that things were going to change. It was just a question of time.

I was asked by Life Magazine, almost immediately when I arrived, to do a photographic essay on Arch Bishop Tutu. I spent weeks with him and his family and I became dear friends with them. I can't speak highly enough about what he is about.

I was asked in 1986 to do an essay on Winnie Mandela and her daughters Zindzi and Zenani. This was at a time when Winnie was still really considered "the mother of the nation" and was internationally revered as this poignant eloquent woman who had continued to carry the torch for her husband who was in prison. I was introduced by a friend who is a legendary Black photographer named Peter Magubane was the man who photographed the Soweto riots in 1967 and somebody who has dedicated his life to covering the anti-apartheid struggle. He was a very dear friend of the Mandelas.

So when Life asked me to do this story, because I was introduced by Peter I was immediately trusted by Winnie and taken in.

We became very good friends. Not only did I spend weeks photographing her and her daughters but we stayed friends and I would go to their home in Soweto often to visit or baby sit.

I stayed in South Africa for three years after what was meant to be six weeks and in 1988 I was the eleventh journalist to be kicked out of South Africa by the apartheid regime. In those days that was a compliment...

DR: Because they thought your work was somehow threatening?

DT: Threatening, yes.

From 1988 until 1990 I was based in Paris and I continued to cover events around the world. I couldn't even go back to South Africa on a tourist visa. I was persona no grata.

Then, in 1990 I get a call from the South African Embassy in Paris from this man who said he was the second in command at the Embassy. He invited me to have lunch with him at a very fancy restaurant. I was wondering what this was all about. I was very suspicious and skeptical but I went along for lunch.

We were there for about five minutes before this man looks at me and says "Things are about to change in our country and we want people with credibility like you to go back and cover these changes." So I'm thinking "What is this about?" The South African government had not only been repressive but very Machiavellian about how they used all kinds of means to slander anyone they conceived of as a threat to government including journalist, so I'm thinking "What is he trying to get me into"? I told him that I would do it on two conditions -

that he give me a visa that has no condition

and

that I get to pay for lunch.

I got the visa, and I went back to South Africa a week later and Mandela was released two weeks after that. Because of my friendship with Winnie and their daughters, I was invited into their home the first night of his release and I was able to witness them at the dinner table for the first time in twenty seven years and I photographed their first dinner at home.

I was invited then with Peter Magubane to travel to America with Mandela on his first visit. It was fifteen days to eleven cities in 1991. I also covered his campaign to be president in 1994 and his inauguration and I have visited with him many times since, including about five trips in the last two years, to do a story about his life for National Geographic which wasn't published in the end.

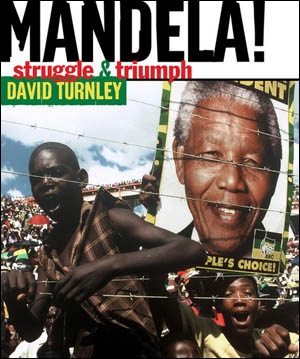

The book that I have just published with Abrams, called Mandela, Struggle and Triumph is a look at the evolution of South Africa over the last twenty five years and at Nelson Mandela's life.

DR: Wow...Out of that whole experience, what was the most lasting impression that was made on you?

DAVID TURNLEY

PHOTOGRAPHY WORKSHOPS

Learn photography on the streets of Manhattan with David Turnley, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Photography

New York City

July 27 - August 3

August 10-17

September 7-14Participants will spend one week working with David, learning to conceive, shoot, and edit a project. David will coach students to move beyond their fears of approaching people to photograph, and will provide detailed instruction on the elements of great photography: light, composition, moment, harmony, enigma, intimacy, lines of energy in a visual frame, and serendipity.

The workshops are limited to 10 people per session and are conducted with individualized, supportive attention for each participant. All experience levels are welcome. A digital SLR camera, perferably with a wide-angle and medium telephoto lens, is required.

The Location: Home to eight million people, New York is one of the most exciting and diverse cities in the world.

During the week, each photographer will be mentored by David to choose a neighborhood, individual, or theme in the New York area, around which they will create a photographic esay that will be shown in a final presentation the following afternoon.

For more details and to express your interest in the course, email David Turnley.

DT: People often times look at my photos in this book and they ask me how it was that I was able to earn such intimate access into the lives of, particularly the people of color in South Africa...

When I went to South Africa in 1985, while I understood the realities of apartheid to be not just tragic but appalling, it wasn't such a distinction from the division that I experienced in my own country and the frustration that I felt. I saw this as an opportunity for me to try and make a statement with photographs about the tragedy of racial prejudice and about fear and the way that people tribalize themselves out of fear. I didn't really have an axe to grind. It wasn't like I wanted to go to South Africa to point out that White people are bad and Black people are great. I wanted to go to pursue this conviction I have had throughout my life, that everybody is the victim of this kind of division. What I was trying to look at was the day to day realities of how that tragedy manifests, and not only what we know to be true, that a racially legislative division is shocking, but that the psychological damage of the master-slave dynamic is so humiliating and indignant to everyone involved.

On the other side of the coin, those manifesting that kind of control -- the master -- are such victims because they limit themselves access to the richness of the diversity of their society.

It was so evident when I got there that people of color were just so unaccustomed to someone who wasn't of color looking them in the eye and extending themselves openly, that every time I did that I was totally welcomed and I understood that there was in no way a sensation that was anti-White. There was a yearning to be treated as human. That gave me an entry ticket into the lives of anyone I wanted to encounter - as long as I had an open heart.

DR: Clearly your view of life informs your photography. How has being a photographer, photographing such intense and often tragic events, informed your view of life?

DT: One of the first things people say to me when the meet me is "You seem so normal and upbeat. You have a sense of humor and you're not jaded". When they say these things I am always sort of stunned because it doesn't occur to me that I wouldn't be like that. But then I try to think about where that presumption comes from. People explain that they think that because I have seen so many tough things I couldn't possibly maintain a sense of optimism. I realize that what they don't understand is that, while I have witnessed a lot of tough things, I have also witnessed the most unbelievable graciousness and generosity.

What I have come away from my experiences with is this awareness of human potential that leaves me convinced and convicted that we can do better as opposed to being jaded that this is the status quo.

DR: So you're saying that you have an opportunity to see more of the whole picture than others...

DT: What I have witnessed...Nelson Mandela is a classic example. Here is a man who was put in prison for twenty seven years simply because he was struggling towards a society that didn't judge people for the color of their skin. He was willing to die for that. He spent twenty seven isolated years in prison for that; twenty seven of his best years in isolation away from a family that he loved and from a society that he wanted to contribute to. You can imagine that he would come out of prison bitter and resentful and seeking revenge. That was the last thing that he manifested when he came out of prison. He came out of prison able to be at peace knowing that what he spent twenty seven years struggling for was freedom, not only for Black people, but for White people too and everybody else. He was struggling for the freedom of people.

DR: And he was in fact a demonstration of the freedom that he fought so selflessly for...

DT: Yeah...

And as I say this I want to caution that I am not being Pollyanna about the injustice that he and so many others have experienced. Its not as if one is meant to forget, but I think the unbelievable glory of that struggle is that it was not about revenge. It was not about turning the tables to now be the oppressor. It was about trying to unleash and celebrate what it might mean to be a country of South Africans in a multi-racial society. They have created a pretty unbelievable constitution now that embraces that.

DR: It seems to me that some of the most optimistic people that I know are people who have been through some pretty terrible things. What they have gone through inspires them somehow to see possibility as opposed to being cynical. Do you consider yourself more of an optimist or a realist as a result of what you've seen?

DT: Those lines are really blurry for me. I think it's probably a combination.

I think I am both a realist, in that I have had the good fortune to witness some very heroic people who have manifested enormous courage and generosity in the midst of real hardship, which gives me the conviction that we have that potential.

But, I was also raised with the dreams of Dr. King, my own parents and so many people that were a part of the Civil Rights Movement and who aspired to something better. So I have never really thought there was another option.

I don't allow myself to imagine that we aren't capable of great potential so I'm not so sure that realism and optimism are distinct. I think that I am a combination of both.

DR: You know what I am gathering as I am listening to you is that perhaps what it is, is that optimism doesn't necessarily require a happy ending.

DT: I understand what you're saying. That is a work in progress for me.

DR: Do you approach your work with an idea or a philosophy about what you want your audience to experience?

DT: I have never felt motivated by the notion of demonizing anybody. I don't take any satisfaction from that. It doesn't equate with my view of people...

DR: But it would seem like an easy default place to go to...

DT: That feels totally misplaced. I don't try to gloss over the realities but I don't try to depict the realities that I'm witnessing as a framing of good guys and bad guys. That doesn't add up for me. I really try to keep in mind that, when there is injustice, we are all victims. And I use my camera, my eyes and my heart to display the tragedy of injustice in a way that we all have the opportunity to get that so that people might be left thinking:

"We can do better than this".

DR: Your approach allows for us, people, to connect with our own humanity and therefore allows us to connect with someone else's humanity, even if that someone else is someone who we were prepared to call "our enemy". Really, we all just want to be human together, don't you think?

DT: I couldn't agree more, Dana.

DR: What have you been surprised to learn about yourself?

DT: After everything that I have just said to you, I have to struggle often times with my own judgments of people; my own need to stay true to a sense of what is right and wrong. I think I am fairly good at not being judgmental and of keeping an open heart. I was raised in a family that was very Liberal and it is very hard for me sometimes to open my heart to the other side. That is a real work in progress.

I am inspired by Obama. I have good reason after spending some time around him and after what I have read and witnessed to believe that what I project onto him is worthy of my projections and my hopes. I think he is interesting in that he not only is his narrative, as someone who is the product of a White mother and a Black father -- not just an interesting narrative but an inclusive narrative -- but I think that he is generally pretty inclusive when it comes to the spectrum of politics in this country.

It forces me to re-examine some of my own shutting down and not being open minded when it comes to "the other side of the aisle". I realize within myself that if I really do feel convinced that we have to strive toward conflict resolution then it doesn't serve my purposes to suddenly shut down toward any group. That's the struggle that I confront on a daily basis.

DR: I know that you've been photographing Barack Obama on the campaign trail. Because I am struck by the opportunity that is before us as a nation to embrace the possibility of an Obama presidency, would you compare Obama to Mandela?

DT: I think about it and I'm not sure I am prepared to articulate some of the things that resonate as similarities. I don't think either of them feel like they have an axe to grind, in fact quite the contrary. I have seen both of them walk into rooms with people of diverse backgrounds and I don't get a sense that they are just putting on a façade. They are just generally at peace with people and don't seem to want to make anybody feel better or worse than anybody else. They are both very self contained and self aware with an interesting awareness of their own wisdom, without being arrogant. Both are extremely disciplined people. They have a sense of their strengths, they are both very humble and I think they are both fundamentally driven by wanting to move our collective story forward. They both have tremendous integrity and they both have a keen sense of having been called to fulfill these missions. They are answering a calling.

DR: It's humbling to be a witness to the events that surround both of these men.

DT: They also both have great smiles and great twinkles in their eyes. That I think is a genuine reflection of peace and happiness.

DR: I have heard it said that the thing that attracts us to other people and that inspires us about other people really comes first from something that we also have within us that is reflected back to us in those that we admire. What do you think it is about you that is reflected back at you by these men?

DT: I am embarrassed to try and answer that question...

DR: But not everyone sees what you see. Not every one sees them as great men. What is it about you that can see that?

DT: The privilege that I have understood in my own life is the joy that one feels when you feel that your life is much bigger than yourself. I see that in both of them.

DR: A hundred years from now what do you want to be remembered for?

DT: I'd like to be remembered by my son as a father who really loved him and gave him everything that I could possibly give him so that he could enjoy his potential and to live a joyful life. That's the most important thing.

And,

as grandiose as this conversation has been about my work, what motivates me more is the sensation of being with my friends and family. I'd like to be remembered for being the kind of person that I am articulating that I want our world to be about - on a daily basis and in my more mundane interactions rather than in the big brush strokes.

Lastly,

as somebody that just stays true to -

a spirit of passion.

Thanks David!

Mandela: Struggle and Triumph

From Amazon.com:

Nelson Mandela, an icon of the international struggle for freedom and equality, whose importance rivals that of Martin Luther King and Mahatma Gandhi, turns ninety in July 2008. Mandela spent twenty-seven years in prison for his opposition to the apartheid regime of his native South Africa. Released in 1990, he pursued a policy of reconciliation, steering his nation into the ranks of the world’s multi-racial democracies. He was elected president of South Africa in 1994.

Photographer David Turnley covered Mandela and South Africa for the world’s press, beginning in the 1980s. He witnessed the turbulence of the last violent years of apartheid, was there when Mandela was released from prison, campaigned with him during the presidential election, and sought out the significant people and places of his life. In Mandela: Struggle and Triumph, he tells in words and photographs the dramatic and emotional story of the most powerful movement for civil rights since the American civil rights movement, through the eyes of its legendary leader.