Dennis Watlington, Emmy Award Winning Writer, Film Maker and Author

Author Dennis Watlington possesses a charismatic magnetism that sets off sparks when he enters a room. As a teenager that electricity attracted best-selling author Gail Sheehy who subsequently included a chapter on Dennis in her 1976 landmark hit, Passages, describing him as a "spirit inextinguishable." That was true then and it is true today. Dennis' resilient heart challenged the limits imposed on a poor black child born in the Harlem projects and built a life and a career doing what many would label the impossible.

Dennis boarded the early Sixties integration train at the age of eleven, when he was selected to be part of a neighborhood boys club program that groomed ghetto children to receive scholarships to exclusive private schools. Criminal behavior clashed with a desire to reach some of the goals that whet his young appetite. Later, a chance meeting with a Hotchkiss School trustee changed the course of his life, and nine months later Dennis was attending one of the wealthiest boarding schools in New England.

After Hotchkiss, Dennis attended New York University.

In early 1979, he wrote and directed his first play, Bullpen, produced by the American Theater of Actors and founded People's Neighborhood Theater, a group committed to bringing diversity to the city's theatrical community.

Dennis had one more bout with hell, when in the early eighties he succumbed to crack. His addiction raged for several months until he entered a rehab determined to kick the addiction. On the road to recovery, he met with Gail Sheehy who suggested he write about his recent brush with destruction, and several months later Dennis chronicled his harrowing tale in "Between the Cracks" for Vanity Fair Magazine. The article was optioned by HBO for a television movie and Dennis was hired to write the screenplay. More opportunities followed in print journalism, and Dennis continues to write for Vanity Fair as well as the New York Times and American Way Magazine.

Dennis has written several Movie-of-the-Week scripts for the networks and ABC Daytime Drama, including All My Children, One Life to Live, and The City. He has several feature film credits.

For the past decade, the bulk of Dennis' work has been concentrated in documentary film. In 1994, he won an Emmy Award for writing The Untold West: The Black West for TBS. Dennis also produced and wrote Walter Rosenblum: In Search of Pitt Street, Sly and Jimi: The Skin I'm In, Unintended Consequences, Hospital at Ground Zero and Zahira's Peace. Zahira's Peace, winner of the 2005 Ciné Golden Eagle Award, is a documentary about a young woman injured in the Madrid terrorist bombing and was broadcast nationwide in Spain to commemorate the first anniversary of the March 11, 2004 attack.

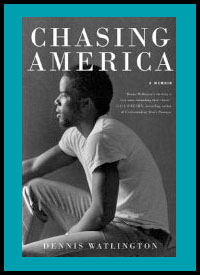

Dennis' book, Chasing America: Notes of a Rock 'n Soul Integrationist is the work of a uniquely American individual. An articulate, funny, energetic optimist, Dennis' world is and always has been propelled by a "spirit inextinguishable."

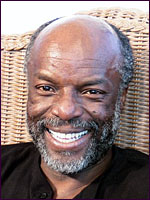

I met Dennis at one of his recent book signings here in New York.

As he walked to the front of the room, sat down on his stool and began to speak, one word came to mind -energetic. As he read from his book and shared about his life, another word came to mind - poetic. So I guess then, that I could accurately describe Dennis Watlington as poetry in motion.

His perfect smile is truthful. His genuine-ness is his genius; Dennis just is who he is, and in listening to him, I gave myself permission to boldly like what I like and be more of who I am.

Dennis has a lot to say and it was a pleasure to be able to listen to his rich experiences. We talked for awhile and after we finished our conversation, three more words immediately came to mind -

warm, friendly and way, WAY COOL.

DR: So, tell me about your life and your work.

DW: I have had an odd, fluke-ish, American life for an African-American born at the time that I was, which was 1952. That was still a good ten hard years before Jim Crow became seriously questioned. That's the America I grew up in.

I came of age right when The Civil Rights Movement really acquired its teeth, the year before The March on Washington, until about '67 or '68 when Martin Luther King won the Noble Peace Prize. That period of time, was the catalyst for African-Americans to emerge from, what was, four hundred years or more of an empty glass. I was lucky that I was in that rise and in forty years, the glass went from empty to half full. Where a half full glass may displease many, half full is certainly something to work from when you and everybody for eleven generations before you, had an empty glass.

There is a person who is going to sponsor one of my projects. He is probably as big in industry and all of that stuff, as you can possibly be, and he is a very good friend of mine. By the same token, the life that I grew up in was as working and lower class, and I only say lower because I am trying to characterize the segment as opposed to impugn the people, but I can go anywhere in that spectrum - ANYWHERE - and feel confident about my right to be an American, clearly understanding what everyone fought for. I clearly understand how much so many people sacrificed for my children to engage in an America that has changed so much. I was one of the pioneers and now I am one of the beneficiaries. A lot of pioneers pioneer…

(Laughing)

DR: …yet don't get to benefit!

DW: (Laughs) …the beneficiaries are plentiful. I was old enough to pioneer and young enough after the pioneering to sort of do pretty well.

DR: Tell me about your work right now.

DW: You have probably never seen a resume with so many different professional forms of commercial communication. I have done everything from writing General Hospital to writing Golden Eagle Award winning documentaries…

I started as a playwright. I wrote a play called The Bull Pen and I can assure you without a doubt, I am the most potent African-American playwright from my generation that you never heard of. That is the play that Bruce Willis came out of, Denzel had a shot in, Giancarlo Esposito came out of it…that is where it started. I am as good as they come.

In June 2011, Emmy Award winning filmmaker and author Dennis Watlington suffered multiple strokes and lived to tell the tale. After two near-death episodes, he managed to say; "Now this is a story..."

Friends of Dennis Watlington is a Special Needs Trust created to provide support to The Rock 'n' Soul Integrationist's inspiring journey of recovery, that has re-united his family and closest friends. With the intention that this unique perspective on one of life's most devastating events, can be a beacon of hope for others in words and film.

To learn more, visit http://denniswatlington.com/

After that I couldn't get a job because playwrights were scarce, black ones even more so. So I took a job writing for Vanity Fair magazine and I took a television job. I had to learn everything because it was the only way that I could get work. As a Black writer, "You were", as Malcolm said "there for as long as you were necessary." You could be brilliant, but once the Black theme that the television show was dealing with was over -

so were you.

I managed to escape that because I discovered that I had talent at whatever I tried. So I was able to survive. But if you looked at Black work in the context of the overall picture and you drew yourself a circle in your mind and you cut maybe a 2% slice, Black writers and all their work, was in that tiny slice and they had no access to any of the rest of the pie.

People would think it was loony in most cases to hire a Black writer to write a White script. It was funny because I lived on a farm with my Irish-Catholic wife and my two bi-racial kids and whenever we would leave the town of New Marlboro we would take the entire Black population with us.

(We laugh)

I tell ya! I couldn't be no more White! (Laughing) How I can't write about White people?!!?!!

They used to have something in the soaps where I was termed a "Black-ologist", which means that when they had a Black theme they would dial me up.

DR: I don't even remember Black people on General Hospital…

DW: Well, I started on All My Children then I went to One Life to Live and I created what turned out to be a community help center in a rough neighborhood and they ran a whole story line through that. They would call me whenever there was some Black stuff. I am imparting this information to you only because it existed, not because I am bitchin'. It's very important that distinction be made because I am too crazy to bitch about those things.

As a writer now, with the growing success of the book, I have been both a well received playwright at the beginning of my career twenty seven years ago and I'm book ending it all, for the moment, as a well received author.

And I'm gonna tell you somethin' --

when I was growing up in Jefferson Projects, I had faint idea what either of those things were. So, I consider myself really fortunate to have had the perseverance to make my own path, essentially.

This is such a transparent, superficial game…When the New York Times says they love you by giving you a Sunday Magazine thing, I mean you transform into Tolstoy, baby!

(Laughs)

DR: Is that what its like?!

DW: Yeah! And I love it 'cause it's all…

…you know only love can break your heart. All the rest of it is stew - very tasty stew -- but only love can break your heart. Other than death, you talk about an equality measure…The wealthiest man or woman or the ones under the most impoverished circumstances share that if and when it occurs…

DR: The heartbreak of love, you mean?

DW: That, "only love can break your heart". And that doesn't necessarily mean the love between man and woman. It could be love of child, love of this, love of that…those are the things that can break your heart. It's almost frustrating because the things that you want most to engage in with, are things that you can't really force or buy. You can't buy love, you can't buy respect, you can't buy trust -- you have to earn them. The most valuable elements in terms of having a life that really matters - love, trust, respect -- you can't buy.

DR: Have you ever had your heart broken Dennis?

DW: To be honest with you, not yet. (Laughs)

DR: Really?

DW: Well, I have had my heart broken in ways other than intimate love. If you grow up in the streets, some of your closest friends, alive-ten-minutes-earlier-gushing-blood-and-dying-within-five-minutes, kind of shit -- that's heart breaking.

My heart breaks for others too, you know. As a matter of fact, I like the fact that I can get fairly misty at times.

DR: What have you gotten misty about lately?

DW: They have been doing a number of things about Jackie Robinson. I am old enough to remember as a child's child, his overwhelming impact and the things that he had to endure. He looked about 75 years old when he was 50; blind from diabetes. He was probably one of the five greatest all around athletes America ever produced. His bother took second to Jesse Owens in the '36 Olympics, in front of Hitler…They never let "us" do nothin' but "we" were symbolic when allowed.

Like Joe Louis was a HUGE BLACK. I mean he was a symbol for Black people and Joe Louis was a boxer. All he wanted to be was a boxer and all he knew was boxing. To have to represent 14 million people -- all Joe wanted to do was gamble away 5 million dollars during the Depression. Ain't that somethin'?! Nobody ain't got nothin' and Joe's got 5 million dollars, gamblin'! Isn't there a rule…?

(Laughing)

Forgive me. I'm just having a little fun.

I have been moving around so much. I just rented this nice little wooden house, which is five minutes from Hotchkiss, where I went to school and I am sitting in the car looking at the house and it is still unfamiliar to me. I feel like I am sitting in someone else's driveway. (Laughs) I just got it ten days ago…

DR: The fruit of your labor…What about struggle? Describe your relationship to struggle.

Dennis and Chuck Griffin

DW: Struggle usually creates a lot of pressure and as my book will tell you, a man named Chuck Griffin, who was one of the great community center leaders of the 60's and 70's in Harlem, was my mentor. My first wife was his daughter. Chuck's philosophy was that,

you want the kids they call incorrigible because if you can peel back that layer, you will find an incredibly competitive, resourceful person.

It's just that you've got to know how to peel. I took a group of those kinds of cats, who everybody said were lost, and made a football team out of them. We won the New York Daily News City-wide Championship, Long Island white people, the whole thing,…we kicked all their asses and won the whole thing. These kids learned complicated football, kind of like theorems, that would certainly qualify for any math class or any of that shit, if their attention level was there.

I know how to get their attention because

- a) I was one of them and

- b) I was one of them who was lucky enough to break on through to the other side and

- c) They had to respect me because I looked and sounded like somebody who could whoop somebody's ass.

I am not talking about using violence, I know all of the "PC" shit, but lookin' like you can whoop somebody's ass is a helpful thing.

Chuck would say, "Get their attention and then smother them with love." These kids are kids! When I look at them I don't see the ones that they show on the news like the ones in handcuffs. I see kids! Everybody is scared of them but they are afraid of themselves… Because of the lenses that they are viewed through, they are already in a real difficult, but not in my opinion, impossible situation and, you can't beat them up! We don't need to build victims, we need to reveal to these kids just how superior they can be.

That is what Chuck did.

Chuck Griffin got him a sign about a hundred feet long that said "No. 1 on the planet earth!" and he brought all us young junkies in off the street. That started that whole transition of him getting us incorrigibles into some of the best Prep Schools in the country, myself included. We knew what he knew! We knew that any of us that had survived the streets…we understood that if we had that side together…we were just frightened as hell about what ever the other side was.

Chuck told us, in effect, that "The only thing we had to fear was fear itself" as apposed to the intimidation that had been passed down from generation to generation about Black people's perception of White people.

Ah…This is my first three free hours in the last five days and it's kind of like I am gushing.

DR: Wow. I feel honored that you are allowing me to intrude on your first three hours of free time. I feel honored and -

guilty.

Chasing America: Notes from a Rock 'n' Soul Integrationist

by Dennis Watlington

Born in Harlem in 1952, Dennis Watlington has been walking a tightrope his entire life. At the age of 14, after bouncing in and out of various schools, Dennis got addicted to heroin. But instead of being another -one trick pony of victimization,+ Dennis kicked his habit and received a scholarship to the Hotchkiss School, where he was elected president of his class. He then went to NYU, grew out his afro and became a different kind of Bleecker Street hippie--part Panther and part Walrus.+Playing against type his whole life, Dennis became involved in film and theater, got addicted to crack, kicked that, and finally pulled it together to become an Emmy winning television writer.And that+s just a thin, thin slice of this man+s story.Chasing America shows us the best and worst that America offers to a black man-from the Jim Crow South to boarding school life in New England to backstage at the Fillmore East to a holding cell in Bellevue Hospital.

Praise for Chasing America:

"And I thought I knew this crazy-brave black boy who bolted out of a Harlem ghetto into a white prep school and bobbed and weaved his way across the treacherous divide between black and white America. But Dennis Watlington's life story is even more astonishing than I knew."

--Gail Sheehy, bestselling author of Passages

"Dennis Watlington has lived more lives more fully than any memoirist I know of. He writes about his many harrowing and exhilarating experiences with kindness, knowledge and an unfailing ability to surprise."

--Sean Wilsey, bestselling author of Oh the Glory of It All

------------------------------------------------

From Publishers Weekly

Watlington was a poor African-American boy in LBJ-era New York City whose intellectual acuity landed him scholarships to several prestigious prep school programs as the "token Negro," including the Hotchkiss School in Connecticut. But the street lured him back; he became addicted to heroin at 13, was in gangs at 15 and incarcerated at 17. Later he was tempted by alcohol and crack cocaine. Watlington's healing came through acting, teaching and knowing the right women: his first wife, African-American actress Gerri Griffin; their daughter, Avery; his Caucasian wife of the past two decades, Anne; the Oscar-winning documentarian Barbara Kopple; and his lifelong friend, Gail Sheehy, who'd written about him when he was at Hotchkiss. Watlington views his childhood, adolescence and rise as a television writer and screenwriter through the scrim of racism. His tale is remarkable, if incomplete (his father and siblings are rarely mentioned, his mother appears only as a vicious harridan, he never explains why he chooses drugs and crime, he glosses over his successes), and the overabundance of colloquial slang and the excessive use of "nigger" make for hard going. Nevertheless, it's a compelling story of one man's struggle to define his place as a black man in white America. (Feb. 15)

Click here for more information and to buy at Amazon.com

Dennis Watlington is an Emmy Award-winning documentary film maker, a television writer, a screenwriter, and a playwright. He lives in the Berkshires of Western Massachusetts with his wife and two children. Chasing America is his first book.

DW: No. This is fun. I mean I don't know how it is going to turn out but, this is fun.

You know I have done a lot of print work. My print work has been translated into at least four different languages. I have done Vanity Fair, Cosmopolitan -- they reprinted my Bruce Willis Vanity Fair piece in Cosmopolitan -- I have written for the New York Times and all those other magazines, and so I understand how difficult a freelancer, a writer who does these kinds of stories - it's a difficult job and so I always try to understand that because I have done so much of it…

DR: O.K.

Well then, I have a couple more questions that I want to ask but I have to admit, again, that I am feeling guilty about your three hours of free time, not that it was your intention to make me feel guilty…

DW: My what? Will you stop that! I am offering you…Do you know how many people interview me? I have had forty interviews over the last sixty days. I am telling you don't feel guilty. I am giving you the time because it is important for me, through your outlet, to express myself!

DR: O.K.! O.K.! I am off of it now. (Laughing)

DW: (Laughing) Thank you.

DR: So then, can you share with me a critical turning point in your life?

DW: There are a handful, like there are in everyone's life. One of them I wrote about in the New York Times February 5th Sunday Lives Column.

I had done about a year and a half of incarceration in various places, OK?

DR: Uh huh.

DW: They sent me to a half way house and then let me out. The judge said "If I see you again, don't even stop because you are going right to "three to five".

Well about a couple of months after that, me and this guy named Stinky…there used to be a school called Benjamin Franklin and it used to be junkie paradise. Me and Stinky had gotten our drugs, gotten our heroin and we ran into this tenement building where we would "get off"; where we would shoot up. We get to the roof and we start to cook up our shit and everything, and we hear the sound of footsteps. They keep getting closer. We throw the heroin bags down the spiral staircase and this BIG BLACK HAND, attached to this LONG BLUE SLEEVE -

caught one.

He comes up and he has us cornered. I bow down on one knee and "sing for my supper". Now I had had a little schooling, so I was trying to use as many big words as I could -- whatever the hell. Of course, this is a vain attempt, but for some reason he looks at me and he said "You! Get out of here!" but he took Stinky and I haven't seen Stinky to this day. I was fifteen.

Had that cop not nodded his head and let me go, then the three years that I wound up spending at Hotchkiss, I would have spent those three years at Elmira.

But here goes the post note:

It was the beginning of my film career. I am about twenty two and they are having the Double Dutch competition down at the New York Coliseum, and I am taping sound for this small crew and I hear

"Hey!" I turn around and it's "Mike the cop".

He's one of the judges for the competition and when he sees me, first of all, there was this huge sigh of relief. He would tell me that, when he let me go that day, he thought about that for a long time. He said that I could have killed someone that night and that he would have been completely derelict of his duty if I did.

I tell him how grateful I am and I said "Thanks. Good cop work." He said "No. It wasn't good cop work,

but it was a good decision."

That was a turning point. That was a real turning point.

Probably one of the biggest turning points of my life was when I came out of Harlem hospital.

I was in there for 2 1/2 months for hepatitis. When I came out I was greeted by my heroin shooting buddies and with the best intentions they want to celebrate by getting me high which heroin addicts never do. So it was a great gesture but….I saw angel wings in the height of the cold turkey and the diseased liver. The pain was so great I saw angel wings swirling above me. Now I know they were an illusion but they were real to me. The pain was so great. I never experienced pain like that before or since.

So when my friends showed up as I was leaving the hospital, I just couldn't deal with that so I ran back in the hospital and hid in the pavilion long enough - junkies aren't going to look for you for long when they want to get high. After that I hid out in my mother's house and rarely ever touched the streets because I did not want to get back on heroin again.

There was a wonderful school teacher named Glynis Pierce, a Black woman, peach skin and beautiful. She lived on 80 something street and in those days anybody Black who lived downtown out of Harlem, that was real heightened stuff, what we would call luxury. She was painting and she said that she would give me five bucks to come and paint.

She put on a Beatles album called The Revolver. On that album is a song called Tomorrow Never Knows. That is when I discovered John Lennon. John Lennon's influence on me is as responsible as anything for me to reconcile getting off drugs as a real street criminal while still being able to maintain sort of the edge of the force of my personality. In effect {his music} told me that I could be a warrior for peace, love and tolerance. That reshaped everything for me. It was like coming out of a closet. I went, for awhile down the hippie thing.

Ultimately I became a hippie in the ghetto, but because I had been such a ferocious criminal, the hard cats chose to look at it as eccentricity as opposed to weakness. It was almost like the Gay guy who comes out of the closet. Only because he is somebody who can whoop everybody's ass, (Laughs) they'll let him be Gay?

Well that was the biggest turning point. If John Lennon didn't hang a sumptuous sized pair of cubes on phrases like "All you need is love" I would never have made it. I can mean that because I can understand how much more powerful that was than violence and the stuff that I had engaged in so regularly.

It established two things for me:

- Independence of thought

and - That I didn't have to kill to be strong and tough

Believe me, that kept me out of the penitentiary or the grave - that realization - because that is where I was heading. That is where all of my friends are -ALL MY FRIENDS. You know I went to a reunion in 2002 and you know how they do "Let's pour out a little bit 'a booze for all of those who have passed"?

We almost drowned.

Me and my friend Noel, who went to Hotchkiss with me, when we went to Hotchkiss together, in the previous 3 ½ years, between us we had over 700 robberies. So, understanding that love, or let's call love sharing so that it doesn't sound so generically whimsical, sharing was so much more powerful than division. John Lennon taught me that and when he allowed for himself to be percentage-ly feminized by Yoko, I was able to benefit from that as well.

When they did the song "Woman is the Nigger of the World" and you thought in terms of the scope of the entire earth, there were few people who were more oppressed than women around the world and men were really raised not to think about that.

You know a very good friend of mine, Barbara Kopple, she is a two time Oscar winner, she and I are like brother and sister. When I met her and Gail Sheehy, - I was about seventeen…

What was significant about that, was that this was the first generation where men like me could have role models that were women that were not their mother because women were starting to do this cool shit, like writer, like film maker.

That was right at the beginning of the feminist movement and both of them were always sticking picket signs in my hand.

Back then, Yoko who was very vilified because she dared to say "I am equal" and John, rather than rejecting that and rejecting her, he learned from it and I, as a result, learned from it as well. That helped me fashion two of the most important parts of my life which was:

- Born in the ghetto in criminality

and - Understanding the multiple layers of contribution that women offer

That happened to dovetail into Roe vs. Wade and all of that stuff. There was this whole new thing happening and John was strong enough to want to learn and I really admired that. I benefited from that.

DR: What are you most happy about right now?

DW: If you knew how I thought you would believe me when I say - this interview…

DR: O.K.?

DW:…Because I am sitting in front of a house that I don't know, but I know I paid the rent and I am free associating with the thoughts that come from your questions which normally I don't do because it's usually a studio thing; the whole kind of canned stuff where you don't really have time to express yourself. You can use four paragraphs if you want to but your tape recorder holds what I think.

Another thing that makes me happy right now is that the book is being received by such a wide range of people that are accepting it kind of like their own. I can do Cambridge and Hue-Man in the same week and draw a huge reception from both for reasons that they ascribe to, what they have gotten out of the book. People really are moved by the opportunity to share what I stumbled upon which was:

A way to be compelling about race without being divisive.

The book kind of forced its own will to express itself that way.

Well, I have exhausted you, my dear.

DR: But wait, I have one more question for you. A hundred years from now what do you want to be remembered for?

DW: A hundred years from now I would want to be remembered as somebody who saw America's greatest years ahead, because of my belief and work with its strength in its diversity. If I have a few pages somewhere on that, then I will really be happy because I think that -

our diversity is our strength.

Thanks Dennis!

Dennis Watlington is not your typical Black man. Chasing America is his story of walking the tightrope of American racial politics and finding acceptance always elusive.

-----------------------

"Chasing America is an epic tale of the black experience in late 20th century America. Author Dennis Watlington has seen it all, and makes no excuses for his addictions, petty crimes and squandered opportunities, but the soul-crushing racism that surrounds him speaks for itself as he makes his way from Harlem and the Deep South on into the larger, white-run world. The life he ends up creating--as a husband and father, as a playwright, actor and writer, and as a friend who never forgets the old neighborhood--are a tribute to his innate decency, his sheer talent and his inspiring capacity for self-renewal."

–Beth Harpaz, author of Finding Annie Farrell

"Chasing America covers many topics from drug addiction, sex, interracial marriages, racism to redemption. Dennis Watlington's experience is a good example of how God deals with us as individuals."

– Armstrong Williams

Click here for more information and to buy at Amazon.com