Matthias Hollwich, Architect

Matthias Hollwich is co-founder of HOLLWICHKUSHERN LLC. HWKN is a New York City based architecture and concept design firm. The office with the idea of de-familiarizing the ordinary. Projects include the design of the first retirement community of West Africa, 2 large-scale apartment renovations on New York's Upper East Side, the Favella Formiga Open Air Theater in Rio de Janeiro, and the reinvention of the city center of Dessau in Germany in the context to the IBA 2010. In the Fall of 2008 the firm's award winning vision of urbanism, MEtreePOLIS, was featured in the German Pavillion at the Venice Biennale, and followed the successful deployment of the MINI ROOFTOP NYC for the BMW brand MINI. HWKN's work has been widely published and was most recently featured in the "Surface Magazine", the "New York Magazine" and "The New York TImes". HWKN is currently working with the University of Pennsylvania on a series of courses and symposia to reinvent nursing home design the culmination in an international conference on aging and architecture in the Fall of 2010 called "New Aging" and also successfully launched ARCHITIZER, a new social networking site for architects.

Before co-founding HOLLWICHKUSHERN, Matthias worked in several internationally acclaimed architectural firms and urban design studios, including: OMA, Rotterdam (Netherlands), Eisenman Architects, and Diller+Scofidio, New York City. In 2001 Matthias founded XPEKT, a concept engineering firm based in Amsterdam. From 1999-2001, Matthias was assistant professor at the Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Switzerland 1999 - 2001 and part of the Bauhaus Dessau Werkstaedte between 2002 and 2006. Presently Matthias is a visiting professor at the University of Pennsylvania. In 2004 he finished editing his first book with Rainer Weisbach at the Bauhaus: UmBauhaus - Updating Modernism.

Last year I saw the documentary film, My Architect and I gained new insight and enthusiasm for the architects as inspired artists. Matthias Hollwich has taken my enthusiasm to another level. His approach to his work is for me, eclipsed only by his "passion" projects. I really enjoyed meeting and talking with him...

DR: Tell me about your work.

MH: If you think about your life, ninety nine percent of your it is affected by architecture.

In America, architecture is driven more by commercial considerations. In Europe, as an architect you are much more of an advocate for society. In Europe you cannot advertise as an architect. Being an architect has the same status as being a doctor. You need to be independent. You cannot act as a pure commercial enterprise. There is a code that you have to kind of swear to when you are an architect because you are for the people. That is what people don't realize. The affect of what you can do in a positive or negative way? You cannot even begin to imagine that as an architect, you could be the reason that a couple breaks up or the reason that someone is unhappy with their lives just because of the way that you have mis-designed a space.

DR: Do you have a different response to your physical environment when you are in New York as opposed to being in Europe?

MH: Absolutely.

New York is something special. The density and the creativity of people resonates and overpowers the opportunistic structure of the city. Here, in New York, it is interesting to notice how people have restructured a city that was basically inhumane and make it a city that works really well for New Yorkers.

In Europe some of the cities have a tendency to be too comfortable. Like I lived in Amsterdam and after a while life was just too beautiful. I like pressure and to be driven and I felt that in Amsterdam I could become extremely lazy. Amsterdam invites you to relax and enjoy life. That was not the right place for. I need a place that provides me with more pressure. Pressure causes me to be more creative.

As an architect I like uncomfortable cities because I like to fix them. I like to be confronted with problems because I like to find solutions.

DR: Tell me about your life.

MH: It is important to know my heritage.

I was educated in Germany, which was kind of a banal education, but then I made the jump to America - Diller and Scofidio and Peter Eisenman. The main affect was working with Rem Koolhaas, Office for Metropolitan Architecture the Netherlands. In America he built the _____ library, _____ and the Prada Store on Broadway and Prince.

What is so interesting about his work is that he revisited modernism and looked into the qualities of modernism and started to enrich modernist ideas with more diverse spaces and with more conceptual spatial constructs. He designs without a preemptive vision of what he is designing, but rather he let the process take shape and with that, he actually shape the building over a period of time. I kind of come from that "school". But what I saw was a lack of an iconographic or a more volumetric expression which I had learned before from Peter Eisenman and then I basically tried to fuse the two things so that there exists a consistent structure of reasoning to develop the inner organization of a building and to also infuse something that makes it aesthetically more pleasing and more interesting as a space.

DR: I am fascinated with the kinds of things you have to consider as an architect that most people just take for granted. Can you talk about those considerations and how they affect the way you approach your work?

MH: First of all, if you take a building in New York:

You have an empty lot. Then the client tells you what he wants. You need to understand what he wants. It could be a little show room or condominiums. Then, in an almost purely scientific way, you have to see what the zoning allows and what the city gives you as a space. Then you have to look at things like the amount of floors you are allowed to build. Then you have to determine how the building codes react to the zoning because codes are about emergency exits and the depth of a building and the length and emergency staircases. You have to learn these things all over again with every new project.

Once you understand the basic objectives, one thing that is obvious is that your creative options just got smaller; you don't have a lot of creative freedom from your client who very often has have a very fixed understanding of what they can offer to the market. New York is the most limited,

"I need exactly this square footage and the kitchen needs to look exactly like this".

I mean even the counter top material is defined sometimes.

DR: Is that because the objective is mostly economics and maximizing space?

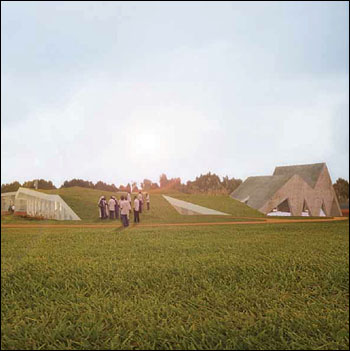

Aging in Africa

LOCATION: Lagoon Aby, Ivory Coast

AGING EXPERT: Emil Klyotta

CLIENT: Foundation Saint Joseph d'Armithia

SCOPE: Concept Design, Schematic Design, Design Development

STATUS: Schematic Design Completed Fall 2009

PROJECT TEAM: Matthias Hollwich, Marc Kushner, Robert May, Marc Perrota, and KymByung Kyun

Aging in Africa sets out to be the first age-valued community on the African continent where the elderly can maintain a meaningful and healthful lifestyle in a comfortable and safe environment. It is a retirement community for Catholic priests who are excluded from the traditional, family based model of eldercare in Cote D'Ivoire. The architecture is shaped by deploying a holistic set of social, economic and environmental sustainable theories pertaining to elder living and care. It is architecture as the caring device. Our hope is that it is an inspiration for a new breed of community that values the efficacy of spirit over the efficiency of care.

For more information and photos on this project, click here.

MH: It's also the sales pitch. The really weird thing is that in America, everybody thinks everybody is an individual but in the end the goal is for mass appeal. People are afraid. The term "Resale Value" destroys any creative flow that the client may have regarding his own home because he is afraid that if he is too much of an individual or too different that he won't be able to sell as quickly and as easily to the next buyer. That is how things have become so generic in America.

DR: What do you think of that?

MH: If you want to live a life for the purpose of reselling something or for the purpose of somebody else's taste then you have already eliminated everything unique about you and your personality.

DR: I mean what is the fun in that?

MH: Absolutely.

DR: That is sad. It's not something that I've spent a lot of time thinking about but now that you mention it, it is absolutely a cause of this homogenous existence.

MH: It is hindering a lot of innovation.

What we try to do is understand how we can work with that kind of standard and push the envelope as far as possible.

What we have tried on a bigger scale is to expand the term of sustainability beyond technology. If you look at the Hertz building, which is on 56th and 8th Avenue, it's the most sustainable building in New York today. When you look at it though, it does not look sustainable. It's a "cool building" but it doesn't resonate like a new type of building and that's actually what we looked into. We tried to do economic designs so that the building itself becomes an inspiration for people to change their way of life and to be inspired by the architecture and to reconnect with nature through architecture.

One of the projects we were able to do was with MINI Cooper where we actually designed a little hill on top of a roof in New York, as an event space. It was interesting to watch people come to this roof and see the hill and see that it had grass on it and to watch them smell the grass and to watch them suddenly change. They were back in nature. They were afraid to touch the grass in the beginning but later after a few drinks they began to destroy the grass (laughs) and that taught us that:

If you reconnect people to their natural world through architecture, you make them overall more sensitive toward their environment.

When you realize the energy consumption per person as a result of just driving, you will be shocked. In other words, driving a car for 15,000 miles uses the same amount of energy as living in the average New York City apartment (heating, cooling, etc.) for a year. It's the same energy consumption. So, if you can persuade someone not to drive so much because their house is so beautiful, that is good. Or, if they become more environmentally conscious so that they buy a more sustainable car or turn the heat down a little bit, that is also good.

DR: So how do you as an architect impact those kinds of everyday decisions that we all make? I mean, "How do I design so that I can impact this space so that the person living here wants to stay home?" You really think like that?

MH: Absolutely!

I tried to synchronize it a little bit recently in a lecture "What are the things we can do as architects to design smaller spaces which are multi-functional.

The other thing is to try to make a space attractive so that people want to be home and therefore they don't travel so much. That also spills into urbanism. If your local store is just down the block you are going to shop there because it's convenient. You don't need the car to go to Wal-Mart.

As an architect we can do a lot to help create a more sustainable society.

What we found out in Germany many years ago is that in office buildings where people can control their own window they are actually more likely to accept warmer conditions in the summer and cooler conditions in the winter, than when they can not control the window. As a result they were able to reduce the heating bill.

There are so many layers which effect user behavior that an architect can consider and on an inspirational level, which I find more interesting than a dogmatic or super imposing fashion.

DR: Right now "sustainability" is kind of a cool and trendy thing. Do you see it as a concept that is catching on in a way that will really matter?

MH: Two years ago sustainability was in everybody's discourse and it was heavily promoted. It kind of died down a little bit because of the recession. The good thing is that the Obama administration is making sustainable concept a driving force for the economy to grow.

DR: Which I think is...

MH: Genius!

DR: So smart...

MH: It's kind of a no brainer. Germany is running on sustainable ideas and concepts right now. What I learned in 1992 in school is not even law here in America, in terms of energy consumption, which was already a law twenty years ago in Germany. It has really created a competitive advantage for Germany because now they are huge exporters of this kind of technology. With America being able to catch up rather quickly based on the tradition that Americans have proven they have, America has a good chance to become competitive.

DR: I think that because of the way that Americans are socialized - to believe that we are always and no matter what, the biggest, strongest, more advanced - has hindered us in terms of keeping pace with progress but, ironically I think that accepting the reality that we are not first in a lot of areas, might be the wake up call that finally has us getting our act together around this issue.

MH: Energy has to become so expensive before people here start to adjust to sustainability. That is what happened in Europe. It's not that people are necessarily more idealistic, it's that the heating bills were just exorbitant. Energy is three times more expensive there than here.

DR: I do think however, that idealism too often gets killed...

What is your idea of a dream project?

MH: Actually we have two projects going on right now. My dream projects are usually the non-paying ones, unfortunately. (I take on a lot of pro bono work).

One of my dream projects is something we are building in Brazil. It's an open theater in a favela. It's it designed for an audience of 750 people. It's a very raw concrete structure in the middle of a favela in a valley. The whole idea was initiated by the government - the NGO of the favela - because they thought that they could change the relationship between them and the residents of the favela by showing what the favela is about. They can take away fear but also they can promote and show off what they have to offer.

When you think about culture in Brazil, it's about Samba and the carnival and all of that is born in the favela. It comes from nowhere else.

With the theater and the stage, which also architecturally for them it was important that it be different and outstanding so that it becomes an invitation for people to come in and experience the culture and to start to create a normal relationship between greater Rio and the favela itself.

DR: What's the other dream project?

MH: The other project is a retirement community for priests in Africa on the Ivory Coast.

I was approached last year at a seminar that I was giving on aging at the University of Pennsylvania. One of the other lecturers was excited about what we do as architects and invited us to become part of this project. In August I went to the Ivory Coast, which has a new energy because they are revitalizing their economy.

The priest who is the initiator, he saw that because old priests don't have a family and don't have home, as they get older they become homeless. He wanted to change this. At first he had the idea of a nursing home and the person who invited us to participate is a consultant in that respect and she told them that they could not build a nursing home because this is what Western society did wrong with respect to its aging population. A nursing home is based on a hospital topology. It is about storing people away. The right approach is not medical. The right approach is social.

The Eden project in America is a much more respectful approach to aging. All of the other 17,000 nursing home facilities in America are basically storage facilities.

DR: My mother in-law has been in a nursing home for the last two years and I couldn't agree with you more.

MH: It's absolutely the wrong topology and it really needs fixing.

DR: So then, what are you doing in Africa?

MH: The idea is that you create residences of groups of people that can self sustain. Urbanistically you have to mix it up so that it is not just an aging community but that ii is integrated into society.

DR: How do you do that?

MH: Well, they are so common sense in Africa. Their approach is not that "we are designing for the elderly", but, "we are designing for us. We are not going to change."

So this priest found a really beautiful spot an hour away from the coastline and there were negotiations with The Chief from this village and basically the one priest asked The Chief if he could get a piece of land for his priests so that they can retire in dignity and The Chief said "Yes! Absolutely. I have a beautiful spot for your priests and I can give it to you for free but what do you do for me?" And the priest said "I see so many children on the street. Why don't I build you a school?

DR: Inside the community?

MH: Inside the community "So that my priests can teach your children". The Chief thought that was a fantastic idea.

DR: They were generating these ideas amongst themselves?

MH: We were just sitting back...

DR: Wow.

MH: It just happened naturally. In twenty minutes they negotiated that free site, school being built, villagers being part of the community in terms of providing food - they become cooks and they get paid for this, the construction is being done by the villagers who will learn new construction techniques so that they can use their knowledge to become contractors for other projects...

It is the first retirement community in West Africa and for us it is important that this becomes a Best Practices example in implementation, operation and design so that it is something that will spread. We are claiming no copyrights. We want to make all of the plans publically accessible so that anybody who wants to copy it, can.

DR: That is so amazing. What is it like for you personally to be instrumental in a project like this?

MH: My grandmother was a Christian. I don't practice myself anymore but there is a culture I have that, not everything I do is for myself.

The architectural education Germany is that as an architect you have an obligation to society. Because we like to take on the kind of projects that have a bigger aim, we are sometimes finding ourselves on the brink of bankruptcy. But, it is more satisfying when I see the positive effect of the work on people's lives.

DR: What do hope that your work will contribute ultimately?

MH: When I studied architecture I was depressed about seeing so much bad work. My drive was to make things better. Period.

Office design used to be about efficiency and functionality. Then people realized that creativity goes down in a corporate environment when offices are too efficient. It was recently introduced that the office coffee bar should be located at the opposite side of the building so that people have to walk, and that the toilet is not efficiently right next door so that people have to walk; so that they have to meet and talk to others, which encourages creativity.

DR: A hundred years from now what do you want to be remembered for?

MH: I am not so ego driven. I don't know if I need to be remembered, but, if I had to say, I would like to be remembered for having inspired young people to do good and meaningful work.

Thanks Matthias!

Formiga

LOCATION: Rio de Janeiro

CLIENT: Ngo Novo Horizonte

SCOPE: Concept Engineering, Schematic Design

PROJECT TYPE: Theater

PROJECT TEAM: Matthias Hollwich, Marc Kushner, Amy Campbell, Jackie Wong, Anja Dornieden, with Dietmar StarkeThe Open Air Theater in Favela Formiga is cradled in a lush valley at the head of a new public pathway that will weave through the Favela below. Formiga will be a new cultural center for an under-served population.

For more information and photos on this project, click here.