Celebrated Photographer, Dawoud Bey

Dawoud Bey was born in Queens, NY and began his career as a photographer in 1975 with a series of photographs, "Harlem, USA," that were later exhibited in his first one-person exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1979. He has since had numerous exhibitions worldwide, at such institutions as the Art Institute of Chicago, the Barbican Centre in London, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Detroit Institute of Arts, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, GA, the National Portrait Gallery in London, and the Whitney Museum of American Art among many others. The Walker Art Center organized a mid-career survey of his work, "Dawoud Bey: Portraits 1975-1995," that traveled to institutions throughout the United States and Europe. A major publication was also published in conjunction with the exhibition. Aperture recently published his latest project Class Pictures in September 2007 and has organized a traveling exhibition of this work that is touring museums throughout the country through 2010.

Bey's works are included in the permanent collections of numerous museums, both in the United States and abroad, including the Addison Gallery of American Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Brooklyn Museum, the Detroit Institute of Arts, the High Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, NY, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and other museums world wide. He has been honored with numerous fellowships over the course of his long career, including the Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship and a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. He has lectured at numerous museum and institutions throughout the United States and Europe. His critical writings have appeared in publications throughout Europe and the United States, and he has curated exhibitions at museums and galleries internationally as well.

Dawoud Bey holds a Master of Fine Arts (MFA) degree from Yale University, and is currently Distinguished College Artist and Professor of Photography at Columbia College Chicago, where has taught since 1998.

Dawoud Bey is someone whose work I admire. His photographs capture the poetry of the human spirit so authentically, which is not surprising when you begin to discover who he is as a person and where he is coming from as an artist...

DR: Tell me about your life and your work.

DB: My first creative form of expression was probably writing. From a very early age, I loved to read, and was constantly losing myself in the world of books. I was fortunate to grow up in a house full of books; we had a set Encyclopedias along with books of poetry. My dad was also a voracious reader, and he had a whole library of books too, everything from various "how to" books to Hermann Hesse's "Siddhartha." So I grew up with a love of words, and started writing poetry pretty early on.

Being a black child in a mostly white school, I didn't know that there were people who didn't think little black boys could be so literate. I remember one time in elementary school the teacher gave as an assignment to write a poem so I wrote my poem and when the teacher called my name I walked up to her desk to show her the poem before reading it. She read it and asked,

"Where did you copy this from?"

Such vocabulary could not be coming from the pencil of a little black boy, or so she foolishly thought. But I kept writing and eventually began publishing my poetry and prose in small literary journals and such.

I got my first camera from my godmother when I was fifteen. It was a camera that had belonged to my godfather, who had passed away recently. I suppose it was my destiny to have received the camera, since I had not expressed any interest in photography at all. She started me on my path by giving me that camera. Getting the camera sure did pique my curiosity, so I had to figure out how to use that camera. I had no idea what all the numbers on it meant, but I started to play around with it, fascinated by the mechanical object more than anything.

A photography class at the local Y was my only technical instruction at that point, and I don't think I learned a whole lot there. Eventually I met a local photographer with a studio in my neighborhood, and I began to learn all of the technical stuff from him. With that I began to try to figure out how to give some coherent sense of form to the things I wanted to photograph; how to shape some aspect of the world that I cared about to the photographic frame.

USA Network Character Project

Click here to watch the trailer for USA Network's Character Project.USA Network announces the launch of Character Project, an ongoing artistic initiative to celebrate the extraordinary people, from all walks of life, who make this country unique. Inspired by USA's iconic "Characters Welcome" brand, and with the support of the not-for-profit photography organization Aperture Foundation, USA assembled a team of 11 world-class photographers to capture the character of America during the summer of 2008. The artists' work will be showcased in the powerful photography book entitled American Character: A Photographic Journey, published by Chronicle Books. The book will be available beginning March 17 in retailers across the country and internationally, as well as at characterproject.usanetwork.com and other major online outlets.

Featuring each photographer's provocative perspective on our nation's most compelling characters, American Character celebrates the continuously-evolving mosaic of our country. The photographs from the book will be on display in a touring exhibition, co-hosted by Vanity Fair, beginning in New York CityThursday March 12 and visiting six additional cities: Washington D.C., Philadelphia, Chicago, St. Louis, San Francisco and Los Angeles. Character Project photography will additionally be featured in a national print, on-air and out-of-home campaign including a 12-page insert in the April issue of Vanity Fair.

- Dawoud Bey: Photographed a diverse cross-section of young Americans near Chicago's Columbia College where he has taught for many years.

- Anna Mia Davidson: Photographed portraits of sustainable farmers in Washington State.

- Jeff Dunas: Shot a color series in and around Los Angeles documenting the American summer experience.

- David Eustace: Shot portraits and landscapes as he traveled along the entirety of Route 50, one of the oldest transcontinental roads, stretching over 3000 miles from the Pacific to the Atlantic.

- Joe Fornabaio: Photographed individuals at barbershops and salons in the New York metro area in order to capture characters engaged in a classic American ritual -- the haircut.

- Mary Ellen Mark: Documented festivals, parades and summer traditions in one of her favorite places to photograph: New York City.

- Eric McNatt: Photographed the "wild and wooly, quiet and intense, quirky and idiosyncratic spirit" of his hometown, Brownwood, Texas.

- Eric Ogden: Shot portraits of captivating and charismatic American musicians who all hail from Michigan, including Iggy Pop, Andrew W.K., Bootsy Collins, Deastro, Andre Williams and Detroit Cobras.

- Sylvia Plachy: Captured the "spirit of the south" through a series of portraits and panoramas in Mississippi.

- Richard Renaldi: Photographed the character of Alaska on its 50th anniversary as a U.S. state.

- Marla Rutherford: Shot portraits of individuals from around Los Angeles who had never before been professionally photographed.

The first group of pictures I made was in Harlem, NY from 1975-1979. My mother and father had met in Harlem, and only moved out to Queens when my brother and I were born, but other friends and family still lived there and we would visit them periodically. We would drive in from Queens.

In 1975 I decided to re-establish my connection to the Harlem community by photographing there. I also wanted to craft my own response to this place that was so rich in history and resonated so powerfully in the artistic and cultural imagination of so many artists, poets, and musicians. Harlem implied a legacy that I wanted to stake my own claim to.

After photographing in Harlem for five years, I knew I wanted to first show those pictures in the community in which the pictures had been made. There is a very long tradition in photography of making photographs in one environment and then showing those pictures in a radically different environment. This only serves to emphasize the sense of difference or otherness contained in the subjects. The subjects end up becoming exoticized. I wanted people who were the subject in the work to also be the first audience for that work.

I had approached the Studio Museum in Harlem with the first group of photographs from the project, and when I thought I had enough for a show I went back and showed them additional pictures. They agreed to show the photographs, and in 1979 my first one person exhibition "Harlem, USA" opened at the Studio Museum in Harlem. It was that exhibition that began my career as an artist.

With the "Harlem, USA" photographs I started out wanting to make a positive image of this African American community but eventually came to realize that rather than a rhetorical kind of positive image I would simply try to make the most honest interesting photographs I could of the people I was meeting. I spent all of my free time waling the streets, letting people in the community get to know me even as I was familiarizing myself with the community I had not been in since I was a child. It was a kind of homecoming for me in a way, and photographing in Harlem for those five years is really where I learned how to make pictures; how to take the experience of the world and translate that through the camera in an interesting and subjective way.

I had looked at a lot of photographs by that time, so I wasn't exactly navigating without a compass. I was only nineteen or twenty years old when I started the "Harlem, USA" project but I had studied the photographs of such African American photographers as James Van DerZee, Roy DeCarava and Gordon Parks, as well as Mike Disfarmer, Richard Avedon, Irving Penn, and whole bunch of other photographers too. So my standards were pretty high, since I wanted to make photographs of my own that resonated the way their pictures did for me. I wanted to like my own work as much as I liked theirs. Eventually I wanted to see my photographs on the wall next to theirs.

DR: What are you grappling with these days?

DB: The work I am doing now started in 1992 when I was invited to do a residency at the Addison Gallery of American Art at Phillips Andover. The Addison Gallery is the teaching museum of Phillips Andover, and I was invited to be an artist-in-residence there for eight weeks, making photographs on campus and interacting with the students there. I honestly didn't know what to expect, and my ideas about what I would find at an exclusive New England prep school were probably just as stereotypical as anyone else's. It turned out to be an extraordinarily productive time for me, and gave me a real sense of how, as an artist, I could make work within an institutional structure. It also gave me an opportunity to make my work as an artist available to a group of young people.

When I was much younger, I had been a remedial reading teacher in a New York elementary school. I had retained a love for teaching, and being in the Andover environment gave me my first opportunity to continue my art practice in an educational environment.

Making work during residencies at various museum and institutions has been the way I've made my work ever since.

We often think of making art as a way to momentarily retreat from the world into the private world of the studio. I was very interested in finding ways for my practice as an artist to actually allow me to be more present in the world; to make my work in a way the was not only aesthetically engaging but socially engaging as well. At the Addison Gallery I converted one of the unused gallery spaces temporarily into my studio and had students come there to be photographed. It was a way to demystify the way my work gets made and to instead make it available to the young people who were students at Phillips Academy. It was also a way to kind of flip the way we think about the museum experience. We usually think of the museum as a place where art gets displayed; I wanted to change that into a space where art is actually made. Phillips Academy was a way to reinvent the institutional space.

I was also interested in creating portraits of these young people that were formally, emotionally, and psychologically compelling, and to give their images a place within the museum. Portraits in museums are usually of those who were privileged enough to have commissioned their own images. Creating the large scale photographs of young people that I make becomes a way of giving them a place on the walls of these spaces, elevating them to the same level of importance. As it turns out, the student population at Phillips Andover is much more diverse than I had originally thought, and the work also became a way to challenge the kinds of misconceptions that people have about young people.

Since the residency project at Phillips Andover, I have done numerous projects working with young people and museums. In addition to making photographs of these young people which are later exhibited at the museum, I try to use my work as a way to provide access to the institutional space for these young people. My most recent museum project was a curatorial project at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, where I worked with twelve teenagers from Baltimore over one month this past summer to curate an exhibition that paired a wide range of my photographs with historical portrait objects from the museum's collection. Having done a number of projects in which I have made photographs of the students while having them engage in other activities around the idea of the portrait and issues of representation, I was curious to see how I might structure a project around a curatorial practice instead of an art making one. This is all a continuation of my long standing interest in de-territorializing the institutional space of the museum, and reinventing it in a way that opens up the possibility for greater participation, multiple levels of accessibility, and conceptual interventions.

My project Class Pictures consists of portraits of a wide range of American high school students, along with self authored texts by each of the students that hopefully creates a rich and complex sense of the individual. I think young people have been depicted in a very one dimensional way within our social culture, and I want to challenge that by making pictures of young people that have a real depth to them, that portrays them as the complex people that I believe they are. Through the book and traveling exhibition, hopefully the work will have a real impact. I do want to impact people's thinking through my work, and I want to impact the way that they think about and regard young people in our society.

DR: Tell me about Character Project.

DB: The USA Network's Character Project also continues my desire to make photographs of young people that have real presence and psychological nuance. All of the subjects in the photographs are students at Columbia College Chicago where I have taught now for eleven years. There was a construction site near the college that had a wonderfully distressed wall on a construction shed that had been erected. I thought it would make a nice background to use as a kind of "studio of the street." Because of how it was situated, away from direct sunlight, there was also this beautiful quality of light in that location all day long. Everyday from sun up to sun down I set up my large format camera and photographed as wide a range of young subjects as I could, looking to create a sense of the diverse population that in fact makes up contemporary American society. I was also really interested in seeing the various ways in which these young people would present themselves to the camera, what kind of persona they would knowingly or unknowingly adopt as they allowed me to momentarily pull them out of the flow of their lives.

DR: What is it that you are celebrating these days?

DB: Of course, mostly I celebrate my brilliant eighteen year old son Ramon. He's a growing artist in his own right, and is developing his talent and love for music along with his considerable technological skills. Growing up in the environment that he has, surrounded by art and creative expression, with two artists parents who have always legitimated and encouraged that, it will be amazing to see what he accomplishes in his own lifetime.

As I get older I think more about how I can continue to make a difference through the work I do, and I how I can use my work and career to create opportunities for other artists who otherwise might be overlooked. I really do believe that one truly empowers themselves by empowering others. And I think I am also celebrating the sense of wonderful possibilities that exist, in terms of things I'd like to accomplishment, places I'd like to see, people in other places I'd love to photograph, stories I have yet to write, programs and events I'd like to produce, and the rich, exciting possibility of it all.

DR: How do you see yourself in relationship to the rest of the world?

DB: When I was a kid, I was constantly badgering my parents, asking them why we never went to any interesting places far away. My favorite question was,

"When are we going to Puerto Rico?"

I have no idea where that came from. Maybe it was from my incessant reading. I always wanted to see what the rest of the world looked like.

Now, as an adult, I feel that the whole world is a possible stage for me, and that I can function anywhere in the world. So I think I belong wherever in the world I find myself, and I think my work is engaged in a kind of global conversation

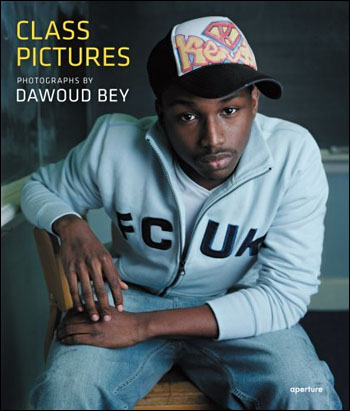

Photo from Dawoud Bey's Class Pictures

DR: That world is changing and right before our eyes, everyday lately. What do you think about the opportunity to witness this change and how would you describe your particular contribution to this changing world?

DB: The extraordinary changes taking place are both technological and social; the level of global interconnectedness between the world's communities is certainly becoming much clearer. Some of these changes are good; I actually do believe that contrary to some people's notion that technology has made us less involved in the physical world around us, I think it has also facilitated--in an extraordinary way--creating, establishing and maintaining relationships through the various online social networks like Facebook. I've reconnected with so many friends that I had lost touch with over the years in this way that it's made a real believer out of me.

On the other hand reading about the demise of print media, newspapers in particular, saddens me. I was reading an article today that talked about the inevitable fact that eventually there will be towns and cities that will not have a single local or regional newspaper. There's something about that that doesn't feel good or right to me, both for what it signifies about a vanishing visible sense of local identity and also the lack of accountability that will result from the decimated field of investigative print journalism as we know it. Of course, my teenage son is remarkably informed and I haven't seen him with a newspaper in his hands in more years than I can remember. So it's probably a generational thing; he gets his information from the web.

As far as my own contribution to this rapidly changing world, I want my work to be a place that suggests that there is still something of real value and substance in human experience and in paying attention the to experiences of strangers; I believe that if I do my work well it allows the viewer to learn something about themselves even as they learning something about the person that I have photographed. Hopefully the viewer takes that sense of engagement with someone that they don't know that my portraits encourage back out into the real world.

DR: What have you learned about yourself recently as a result of your work--photographing someone you didn't know?

DB: For the most part all of my photographs have been made of people that I don't know before photographing them. I actually get to know them through the process of photographing them. Hopefully I am able to describe some aspect of the inner person.

What I think I have learned about myself in the process is that I do have the ability to create a momentary set of circumstances in which someone is comfortable allowing me to look closely at them through the camera, and doing it in a way that is not intimidating. I am able to put people at ease in what is basically an unnatural situation, one of having a large camera on a tripod pointed at you. How to get people to still reveal some aspect of themselves, gesturally and psychologically, is something that I know how to do, and that I think I'm good at. It's partly about being a kind of psychologist and partly about being empathetic observer. I feel that there is something interesting about everyone, and what I know how to do is how to describe that through making pictures.

DR: When people look at you what do you want them to see?

DB: Well, there's no way for them to know just from looking at me necessarily, but I would hope that they would see someone who is trying to make a difference in the world through the work I have chosen to do, someone who is trying to live their life with integrity and a clear sense of intention and mindfulness.

DR: So, then if you were to measure your success according to the way in which you hope people see you, would you say that you are in fact successful?

DB: Since my work has been shown in more museums and galleries than I can think of off the top of my head, I have to believe that a lot of people are responding to my work, and that they are moved by it. By that measure I am definitely successful.

I came of age in the late sixties, and back then there was a saying, "You're either part of the solution or you're part of the problem." I don't necessarily see things as so black and white now, but I do want my work to be a part of "the solution."

DR: A hundred years from now what do you want to be remembered for?

DB: Not that this is something I think about, but if indeed my work is around in 100 years, I hope that it reminds people of -

what one person thought it meant to live a committed life.

Thanks Dawoud!

Dawoud Bey: Class Pictures

For the past 15 years, Dawoud Bey has been making striking, large-scale color portraits of students at high schools across the United States. Depicting teenagers from a wide economic, social and ethnic spectrum--and intensely attentive to their poses and gestures--he has created a highly diverse group portrait of a generation that intentionally challenges teenage stereotypes.Bey spends two to three weeks in each school, taking formal portraits of individual students, each made in a classroom during one 45-minute period. At the start of the sitting, each subject writes a brief autobiographical statement. By turns poignant, funny or harrowing, these revealing words are an integral part of the project, and the subject's statement accompanies each photograph in the book. Together, the words and images in Class Pictures offer unusually respectful and perceptive portraits that establish Dawoud Bey as one of the best portraitists at work today.