Celebrated Poet, Jimmy Santiago-Baca

Born in New Mexico of Indio-Mexican descent, Jimmy Santiago Baca was raised first by his grandmother and later sent to an orphanage. A runaway at age 13, it was after Baca was sentenced to five years in a maximum security prison that he began to turn his life around: he learned to read and write and unearthed a voracious passion for poetry. During a fateful conflict with another inmate, Jimmy was shaken by the voices of Neruda and Lorca, and made a choice that would alter his destiny. Instead of becoming a hardened criminal, he emerged from prison a writer. Baca sent three of his poems to Denise Levertov, the poetry editor of Mother Jones. The poems were published and became part of Immigrants in Our Own Land, published in 1979, the year he was released from prison. He earned his GED later that same year. He is the winner of the Pushcart Prize, the American Book Award, the International Hispanic Heritage Award and for his memoir A Place to Stand the prestigious International Award. In 2006 he won the Cornelius P. Turner Award. The national award recognizes one GED graduate a year who has made outstanding contributions to society in education, justice, health, public service and social welfare.

Baca has devoted his post-prison life to writing and teaching others who are overcoming hardship. His themes include American Southwest barrios, addiction, injustice, education, community, love and beyond. He has conducted hundreds of writing workshops in prisons, community centers, libraries, and universities throughout the country.

In 2005 he created Cedar Tree Inc., a nonprofit foundation that works to give people of all walks of life the opportunity to become educated and improve their lives. Cedar Tree provides free instruction, books, writing material and scholarships. Cedar Tree has an ongoing writing workshop in the Albuquerque Women's Prison and at the South Valley Community Center. Cedar Tree also has an Internship program that provides live-in writing scholarships at Wind River Ranch, and in the south valley of Albuquerque. The program allows students, writers and poets the opportunity to write, attend poetry readings, conduct writing workshops, and work on documentary film production.

Baca is currently finishing a novel, a play and three poetry manuscripts to be published in 2007. He is also producing a two hour documentary about the power of literature and how it can change lives.

With a fundamental understanding of the power of reading and writing and a profound commitment to infect his communities with this understanding, Jimmy Santiago-Baca alters the predictable.

A poet, Jimmy is surprisingly a man of few words when it comes to singing his own praises. He is modest about the fact that he inspires and yet he is very clear about the difference that he makes everyday.

Sincere in his intent and uncompromising when it comes to his principles, Jimmy Santiago-Baca is helping to change lives, person by person -

with words.

DR: Tell me about your life and about your work.

JSB: We have a company called Cedar Tree, Inc.

We go into prisons and work with men and women teaching them how to read and write. We also have an internship program for men and women who are showing some intrinsic motivation to write and to be a part of their community. We go into schools and universities all over the country to give talks and do workshops. We require all of the people that we work with have a book in progress and their job is to get that book published.

We also have a production company where we produce documentaries for the Department of Education. We go and teach high risk kids, kids who just don't want anything to do with school. Those are the places that we go to and we try to get those kids to see things from an entirely different point of view.

DR: What would you say is the best part of what you do?

JSB: Being surrounded with so many good people and watching them grow and seeing the effects of their commitment on the people that we work with. And, while I haven't written in a couple of years, I love writing. That is one of the things that makes me happy. I love what I do.

I do things that are not based on monetary value as much as it is based on my value as a human being. The things that I do give value to my value.

DR: What is the "big pay-off" then, for you?

JIMMY SANTIAGO-BACA BOOKS

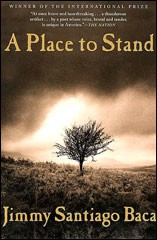

A PLACE TO STAND

From Amazon.com:

Anyone who doubts the power of the written word to transform a life will know better after reading poet Jimmy Santiago Baca's wrenching memoir of his troubled youth and the five-year jail stint that turned him around.

When he enters New Mexico's Florence State Prison in 1973, convicted on a drug charge, Baca is 21 and has a long history of trouble with the law. There's no reason to think jail will do anything but turn him into a hardened criminal, and standing up for himself with guards and menacing fellow cons quickly gains him a reputation as a troublemaker. But there have already been hints that this turbulent young man is looking for a way out, as he painstakingly spells out a poem from a clerk's college textbook while awaiting trial or unsuccessfully tries to get permission to take classes in prison.

When a volunteer from a religious group sends him a letter, contact with the written word unleashes something in Baca, who starts writing letters and poems with the aid of a dictionary. Reading literature shows him possibilities for understanding his painful family background and expressing his feelings. Poetry literally saves him from being a murderer, as Baca stands over another convict with an illegal weapon, ready to finish him off, and hears "the voices of Neruda and Lorca... praising life as sacred and challenging me: How can you kill and still be a poet?" Baca has a year to go on his sentence, but the reader knows at that point he has made a choice that will alter his destiny.

Without softening the brutality of life in jail, Baca expresses great tenderness for the men there who helped him and affirms his commitment to writing poetry for them, "telling the truth about the life that prisoners have to endure."

Click here to learn more and purchase A Place To Stand.

IMMIGRANTS IN OUR OWN LAND

From Publishers Weekly:

The rural Southwest landscape of Baca's short stories is inhabited by outsiders: drug addicts and convicts, absentee mothers and runaways. Baca's first collection of fiction (he is the author of the memoir A Place to Stand and several books of poetry) paints a picture of Chicano life that is at once cruel and sweetly redemptive. In the best of these eight stories, gritty realism is deftly leavened by flights of lyricism. In "Enemies," a trio of newly released convicts find their hostilities giving way to fear and tenderness; in "Valentine's Day Card," an orphan becomes engrossed in a fantasy that his mother will come for a visit. Other stories are allegorical and softer around the edges. In the fairy tale-like "Matilda's Garden," an elderly farmer mourns the death of his beloved wife by working the land she cultivated. In the title story, the couple's three children-a lawyer, a cowboy and a former graduate student-fight over the farm they have inherited…Baca has the ability to convey much in few words, and his precise use of detail delivers small, startling truths.

Click here to learn more and purchase Immigrants In Our Own Land.

JSB: Well, we make money. We have people contribute money to us all of the time. But we have never applied to a government agency and we won't accept money from huge multi-billion dollar corporations. They have offered us money but I just don't want to fall in that box -

"Oh, he has given me his approval that I am a writer."

The approval that I want is when I go into a school that has never had a writer visit and I walk in to a room where none of them want to speak but by the time I leave all of them feel important and want to express themselves. That is the pay-off for me.

The money that we do accept, we accept from individuals who know what we are about and who themselves have come up from a hard street life and who have made millions of dollars. They'll invite us to breakfast and say --

"Here's a check. I really believe in what you are doing."

These really big foundations that have huge names in the literary world will call to tell us that they are nominating us for an award. I tell them not to bother nominating because I won't accept it. They tell me that these awards are given to the best writers in the world. I think that's great because they probably deserve it and I need the money but I won't accept it because of their investments.

DR: Describe the point in your life when you decided to be a writer.

JSB: A friend of mine said to me once that he woke up one morning and found that he had painted himself into a corner.

I had this farm and I got up one day and I said

"Wow! This is it! The bells are tolling. I can't do anything else but this."

So, I began to throw myself into the arena as a serious writer. It was weird because even though I thought my writing was parochial or provincial at best, I started getting letters from all over the world from all over the world from really amazing writers telling me that they really enjoy my work.

That was a really beautiful affirmation.

DR: What do you think that the people that you work with say about you and the impact that you have had on their lives?

JSB: I don't know.

When I show up I tell people that I don't necessarily bring good tidings.

"What I am here to tell you is that you are going to have to work twice as hard as anybody else because you are poor. You're poor in spirit because you don't believe in yourself. I am here to tell you that your spirit is as big as the planet. You just have to take off the shades, man. My job here is to tell you that you are going to have to work harder than you have ever had to work."

The second thing I tell them is:

"You have an experience that is so rare that if you were ever given the resources and the tools to express it in a community forum, people would just congregate around you for answers because we are looking for answers."

The same old answers

"All White people hate Blacks"

"Blacks sell crack"

"Mexicans do this or do that..."

All of those "answers" that people have given us, do not work. They work for the people who are running the world but they don't work for the community. I tell them that racism is unacceptable because it is killing us. You might think its cool but it does not work for us. Then I tell them that they have to start all over again with compassion. You can't be cynical. Even though they don't teach compassion at school, I am here to add it to the curriculum.

Courage.

Courage is a crazy thing. Every gang banger I know has phenomenal courage. I ask them

"How about having the courage to redo the curriculum in your school? How about organizing yourselves and do the research so that you can select the books and take them to the department of education and let them know that these are the books that you want and if they don't give them to you you're going to shut the school down?"

Half of the teachers are sorry I came and the other half are like

"Yes! Right on!"

Teachers love students who love to learn...

DR: What's the wisest thing anyone has ever said to you?

JSB: "No one has the right to oppress anyone else."

DR: And who said that?

JSB: An old man who was dying in his bed in Chicago.

He had worked hard all of his life. He was really smart but had never gone to school. I asked him what the one thing was that he could tell me that I could carry in my heart.

He said:

"No one has the right to oppress anybody else."

I thought that was beautiful.

DR: What was the wisest thing that you ever said to anyone?

JSB: "Take care of yourself."

The whole colonial thing from way back when, gets deeply buried into the archetypal psyche and because we don't live up to certain standards imposed by others, we think that we should revile ourselves. That's really where the alcoholism and drug addiction and fighting and all of this other crap comes from -- revulsion; revulsion against our spirits.

We have to learn at a very early age that we should have streets named after us. Not after some rich tycoon who bought oil. If your parents and your ancestors built this city, you ought to have a street named after you.

DR: What do you consider your global contribution to be?

JSB: I have to tell you that I am amazed by these beautiful sound bites that people come up with when they are asked hard questions like that - amazing sound bites.

I have no answers for what my contribution might be. All I know is that working hard and the process of working everyday is the answer to what I am contributing. Just getting up and working hard, washing dishes, writing a book, on and on...doing documentary films, helping editing this or that...just doing it!

We show up at a place and a thousand people show up and then we show up at another place and a thousand more people show up. Where do all of these people come from? I am realizing that there are a lot of people who are recognizing what we do. It is really cool to go to a theater and see people hanging from the rafters. We get invitations at least two or three times a week and we are fully booked in fifty cities. We cut the itinerary to fifty so we can't do any more...I guess my contribution is -

to teach people how to read and write and how to take control of their lives.

DR: Writing is a very powerful thing for sure?

JSB: BEAUTIFUL?

DR: Powerful, beautiful...just to be able to communicate effectively is critical. We see the consequences in people's lives when they don't have the ability to communicate.

Tell me, a hundred years from now what do you want to be remembered for?

JSB: With that you've got me speechless.

It would be kind of cool if a man or a woman would sit down a hundred years from now and say:

"There was this guy named Mr. Baca who taught your great grandma how to read and write and that's why your father became a Noble Peace Prize winner."

Something like that would be so cool for me because nobody in my family could read or write - nobody, none of them. I am the only one. Nobody in my family could read or write. Not my brothers or my sisters - nobody.

So, a hundred years from now if a great grandfather would sit down and say to his grand kids that there was this man named Mr. Baca who used to go door to door to teach people how to read and write....

Thanks Jimmy!

Cedar Tree, Inc.

Cedar Tree, Inc.

The revenue accumulated from the books/merchandise page on Dr. Baca's original website will help fund the Cedar Tree Inc., enabling the organization to host more book drives, take on new interns, give more book scholarships, and to help eradicate poverty in the United States through education.

Cedar Tree's longest running program is the Prison Literacy Project, which offers instruction in reading and writing to prisoners and supplies them with books. Dr. Baca has led writing workshops in prison for over thirty years. Literacy gives prisoners a constructive, expressive outlet and reduces recidivism.

A newer Cedar Tree program offers all expenses paid writing scholarships. This program gives writers of all walks of life the opportunity to finish writing their book in Watrous, New Mexico. Participants conduct their work in the calm of a canyon at Wind River Ranch.

In coordination with the South Valley Community Center, Cedar Tree is also leading a writing project for children of Bernalillo County.

There are numerous other programs that Cedar Tree is currently involved in or is planning, all of which could use your help. All donations to fund Cedar Tree, Inc. are greatly appreciated.

To make a donation please send to:

Cedar Tree Inc.

PO Box 9311

Albuquerque, NM. 87119