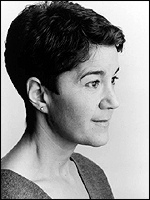

Laurie Gunst

Laurie was born in Richmond, Virginia in 1949. Her growing up coincided with the struggle for civil rights. Since she was raised in a family of "deeply narcissistic (but admirable) Jewish liberals", by a small phalanx of powerful African American women without whom she says she would have perished from loneliness and neglect, her public schooling and her real education were seriously at odds. She learned early just how personal the political could be.

Laurie went north to Boston University, where she eventually flunked out. She crossed the continent to California, seeking to put as much distance as she could between herself and the scene of her defeat, but she came back east in 1971 on fire with the women's movement. She attended The University of New Hampshire, where she finished her undergraduate degree in 1973 and earned a Master's Degree in history the following year. In 1974, she entered graduate school at Harvard University. She earned her doctorate in 1982.

By that time, she had begun spending long sojourns in the island of Jamaica. Laurie slowly became aware of the bitter reality that lay behind the island's paradisiacal façade-the poverty and violence which the vast majority of Jamaica's people suffered-and this awakening re-ignited the passion for justice that had been so much a part of her youth. She became determined to write an expose of Jamaica's brutal politicians and their secret symbiosis with the island's deadliest outlaws, whom they armed and paid to control the slums of Kingston. She moved to that city in 1984, spent two years there tracking these gangs, then came to New York City in 1987 to continue her research. Born Fi' Dead, the story of her descent into this contemporary hell, was published by Henry Holt in 1995.

Laurie's latest book is Off-White, the story of how her childhood against the backdrop of racism in America's South. "Off-White is the story of my southern family-black, white, and Jewish." -- LG

Laurie will be teaching in the spring at New York's New School University . She currently lives in New York City with her husband.

Laurie Gunst is someone with a rare perspective on a very relevant topic - Racism. Her background offers a unique experience that she generously shares with the readers of her books.

We talked about a number of things. Mostly, I just wanted her to "let it rip".

"Don't give up. Keep on trying." Laurie reflects on this line from a Langston Hughes poem.

"I think very often when you see people who have achieved, whether they have published a book or whatever their achievement is, you often do think that they were sort of born to this. And my life has been, not an economic struggle, that I have been spared indeed, but it has been an emotional struggle from the cradle until where I am now which is in my 56th year.

There has been an enormous amount of overcoming and getting over and healing and putting back together -- mending. That is what I would most like to share when I talk about my own life and my work because I think that's what really touches the hearts of other people. I mean, you don't need to see somebody who's "successful" without understanding what it took them to get there. So that's I guess my first offering."

DR: Well will you start then by sharing with me what you want me to know about what you do.

LG: Well I have always, I think without knowing it...my mother would say "Oh sweetheart, you are so political." God rest her soul. She passed on three years ago. She was very political in the best of all ways and I think my work has followed that instinct. I have always been - what's that wonderful line from Lauren Hill's song? I just heard it quoted at a conference on Saturday at The New School about Katrina. "To put the focus; to shift the focus to, not the lowest but to the poorest... to the ones who are most in need and most in want. Those of your readers who know Lauren Hill's music will absolutely know that. I guess unconsciously I have always felt a deep need to do that because I have always felt in touch with those who do not have power; those who are persecuted, those who are in trouble.

Yesterday I was walking down Madison Avenue and a man was begging and I walked by him, which I usually do. Two steps away in the bookstore...on display was this picture of a mansion in Newport Rhode Island with a gaggle of debutantes on the lawn and I looked at that picture and I looked back at that man and I turned around - there was something about that picture that triggered me. You know this horrible disparity between privation and privilege in this country and I thought "How can you pass by this man!" And I just wheeled, turned on my heels and went back and gave him something. He looked up and he said "Thank you sister." And I said "God bless you, sir". You know because just in that moment someone who's down on their luck knows that someone cares. That's all that matters is, that heart-to-heart connection. There must have been something in that photograph of those rich, rich ladies on that rich, rich lawn, in their fluffy dresses, never knowing a moments worry about where the next meal was coming from. Those are the moments that continue to strike me and I know that it has to do with having been raised the way I was raised, which was by very liberal, very right thinking Jewish parents -- I use "right thinking" in the sense of good hearted not "Right Wing" because they were anything but -- and partly raised by this extraordinary woman of color, Rhoda Lloyd, who took care of me from birth onward and who also knew five generations of my family at the time when she went home at the age of 92.

So that was a very, in the deepest way, I think, privileged experience. It was gifted in that, although I grew up fortunate, I was very early on led to see lives way way way beyond and outside my own. The longer I live Dana, in this Republican America, the more I realize how rare a gift that is.

DR: To be able to be connected with the two worlds?

LG: Exactly. To be able to at least imagine and compassionate with worlds beyond my own.

DR: Auguste and I were talking about you last night...and that was one of the things that Auguste had said to me "I wonder what inspires someone who has grown up without having to worry about anything really, what inspires them connect with the poor?" Because there are a lot of people who are raised by...

LG: ...women of color.

DR: ...poor women of color who do not necessarily share your commitment.

LG: I think that being Jewish had an enormous amount to do with this. It's interesting because the old saying is "Northern Jews behave like Jews." ...They are more likely to be involved in the Civil Rights struggle because they see themselves as being Jewish and therefore, as having a role to play in the liberation of mankind. Not to fudge it. I think that's a basic Jewish feeling. It's like what Jesus said "In as much as you do it unto the least of my creatures, you do it unto me." That's a very profound feeling. So the saying was "Northern Jews behave like Jews and think like Jews, Southern Jews think like Southerners", which was very often true. During the Civil Rights struggle, a lot of Southern Jews did have their heads in the sand because they were recently assimilated and accepted and they didn't want to rock the boat. My family was different. They were very involved with social justice.

My mother came this close to joining the Communist Party in the 1930's. She, when I was a kid growing up, was a very involved member of The NAACP, The Women's International League for Peace and Freedom... I mean she was involved with just about every human rights struggle there was. But I think the cause of justice and equality for African American people was closest to her heart. That was very unusual among the Jewish people we knew. They all had African American women who worked for them, and I don't think that they felt a deep -- not only a moral responsibility but a really "heartical impulse" as my Jamaican Rasta friends would say, a "heartical impulse" to do whatever they could to right the ancient wrongs.

My mother put through college, a young and gifted African American child who was the daughter of the man who worked for my father as a gardener. She was the niece of the woman who worked in our family as a cook. My mother met this young lady whose name was Carrie Jefferson. She is now Dr. Carrie Jefferson-Smith, Assistant Professor of Social Work at Syracuse University.

We met Carrie when she was 6 years old. When she was 12 years old, mother made her a promise that changed Carrie's life, which was that mother would put her through any College to which she was accepted. Carrie went to Hampton and then went on to Howard for her Doctorate and she was the first member of her family to be able to stay in school past 8th grade or high school because they were poor folks and they all had to go to work very young.

This is all very unusual, Dana. And this wasn't necessarily a political thing that my Mother felt. It was emotional. It was from the heart. So that's how I grew up. That was how we saw our Jewish-ness.

DR: My suspicion is that, and I assert that one of things that has people be not only successful but happy in life, is to have something beyond themselves that they are committed to. That is my assertion. I am wondering how that might have played out in your life.

LG: It is playing out right now, in that in the aftermath of publishing Off White, I am searching actively for a way to continue to be a facilitator of dialogue because what this book is, I have seen, is a lightening rod.

When I read from it, when people read it - African American people, White people, whatever, North South, wherever -- this book seems to evoke extraordinary emotions and memories among those who have lived this intimate and yet, very painful relationship between women of color who give care to children of privilege, and the children of privilege. I have seen what a wonderful thing it would be to keep this dialogue going. That is something bigger than me and at the moment I am trying to find how to best be used in this capacity because I do think I had an unusual growing up.

I think I was given to experience things and to feel feelings - not ideas. I mean of course the idea of social justice and racial equality is a beautiful thing, but I think it's when you feel it in your heart that something moves; something happens.

This marvelous lady called Claudine had just come to work for us and I adored her. We were sitting in the kitchen one afternoon...this was my "Zen whack"...

I was a very fat child. I ate a great deal trying to fill a hollow place inside me which was there for all sorts of reasons. I spent a lot of time in the kitchen with Claudine because she was an ample bodied woman and she didn't torment me about my fatness the way my mother and sisters did. I was sitting in the kitchen with her one afternoon. She was plucking the feathers from the bird that my father had shot -- he was a hunter. She was humming to herself standing by the sink. I was sitting by the kitchen table counting the bottle return change from the milk bottles and coke bottles that we used for lunch money and bus fare, and stuffing myself with potato chips, pretzels, Oreos - anything I could lay my hands on and Claudine looked over at me and said:

"Mmm. Mmm. Mmm. Just like we always say, 'Negroes always singin' and workin'. Jews always eatin' and countin' his money".

Wow!

That was like "What?!" I literally felt like I had fallen out of a tree...It was a moment when I realized "Wow. You mean this is how Black people see Jews? They don't think we're better then than the Gentiles? They don't think that we treat people of color with more dignity and respect?"

No!

I went upstairs because I had to talk to someone and I wasn't going to tell my mother because I knew I might get Claudine in trouble. I found my sister in her room where she was doing her homework and my sister, God bless her said, "Well Claudine was just telling you something about how her people see our people".

I went around for days, weeks months, years, after that just thinking, "Wow! Girlfriend you have got some pondering to do because this is not what you think it is and all Black people don't love you 'cause you such a sweet l'il thing".

The upshot is that when Claudine was in her late 80's and we had stayed friends over all these years. I would spend a lot of time with her whenever I went back to Richmond. She didn't die until she was 94, almost a year ago, and we remained close right up until her death.

But one afternoon I was talking to her...40 to 45 years after this event and I said "Dine-y, I just gotta ask you something." And she knew before I opened my mouth what I was going to ask! And she said: "Oh Lord child. Have you been holdin' on to that all of these years?" And I said "Of course I have. It's the most amazing thing that anyone has ever said to me. It's why I am writing this book. Was that really a saying or did you just make it up on the spur of the moment. She said "Lord, it wasn't a saying. I was just in an awful mood that day. I can remember it like it was yesterday. I hated plucking those damn birds! It reminded me of when I was a child on the farm and my Daddy always made me wring the chicken's necks and I hated. Plus I remember I had my monthly's.

Who can argue with that?

There were moments like that throughout my growing up...where I woke up to the fact that there was this world out there that was full of pain and sorrow and inequality and Jews were not always "good guys". People of color were not all perfect. That was the hardest to give up. When you grow up in a society as racist as the Jim Crow South was in its dying days, you tend to over compensate. You really do tend to turn people of color into saints and, nobody is perfect. That was the hardest I think for me. I still can't do it. I still overcompensate in that way.

DR: I am wondering if I can go backwards a little bit.

LG: Absolutely. Go in any direction you want.

DR: O.K. You mentioned something about overcoming things in your life and I was wondering if you could talk about one thing in particular that you've personally had to struggle with and overcome and move beyond.

LG: I think the hardest was having an emotionally distant mother. I could add to that a chronically alcoholic dad who never did find sobriety. He lived to be 97 and he stayed an alcoholic until his death. But I think the experience of having a mother, who was not only emotionally...detached against her own will - I think that she wanted to love me but she was so envious of and competitive with me for my dreams and my chances in life to go to college, to choose to be single, to marry as late as I wanted whatever -- that she sabotaged me as much as she could.

The classic experience was when I was wanting to go to college and my dream was to go to Radcliffe, which I could have attained because I was a bright kid and I was a Jewish kid from Richmond, Virginia and it was 1967 - I mean Holy Cow! Harvard would have gone down on its knees. And she said "I hate to tell you this darling but I really don't think you are Radcliffe material".

There was this constant sabotage from her.

I grew up very lonely. I grew up not really knowing what it was to be loved by my own mother. At the same time I knew she was an extraordinary human being. She was wonderful politically. She was a social activist. She was beautiful and glamorous and loved by my father, although he took a mistress when he was in his sixties. That was another devastation in my family. She remained part of the family until his death. That was an involvement that lasted 30 some years.

Those were just a few of the emotional crisis that I weathered in life. I also got through substance addiction. I became a marijuana smoker when I was in my 20's, partly as a result of spending a lot of time in Jamaica and hanging with wonderful Rastafarian elders and teachers who became very important to me. My first book was about Jamaica... Born Fi' Dead.

I think in some ways, to be totally frank, my experience with drugs Dana, was what I mistakenly thought, and I emphasize the word mistakenly, {what I} mistakenly thought was my ticket of acceptance among poor people, African America people. I think I made that classic White mistake, which I freely confess because I think that it is very important to say this, of thinking that drugs were hip because we thought people of color did them.

Marijuana led to cocaine and one of my absolute favorite moments in Off White was when I met and spent an evening at this party that I gave with the great world music genius Jimmy Cliff. This was a party where everybody was doing coke, except him. He was the first person I had ever seen turn down cocaine. When he did, he didn't do it in a snobby way. He put his hand to his chest and said, "I can't. Me voice. I have to protect me voice".

I realized that not everybody hip did drugs. I had been wrong all theses years that it was identified with acceptance by people of color. When I worked on this book in Jamaica, I spent a great deal of time in Kingston's ghettos and everybody was doing one substance or another and that was a big weaning for me. It took a lot of courage to say, "I don't have to do this, you know. I can be who I am. Drugs do not have to be a part of my journey. They do not have to be a part of my closeness to people of color. I can be respected and have dignity as someone who is straight". It sounds like a silly small thing but I think a lot of people, black and white who have made the journey into recovery have to find this truth.

I have known a lot of white people who have done work on the other side of the color line and the class line and they have often fallen into this trap of thinking "I have to take drugs or these people won't think I'm cool -- they won't think 'I'm down'". I think its very important Dana, for people who have had a "druggy" past to speak about it openly and honestly. How are we going to teach our children that they don't need to do this if we don't talk about it? We are so censored nowadays. I mean this Republican homogeny has made us all feel that we have to keep this secret. You can talk about being an alcoholic but you can't talk about doing what everybody did in my generation which was drugs. I am a child of the '60s for Pete's sake. And that was my historical experience...Look at Richard Pryor's unbelievable riff on free base...Where would I be without remembering Pryor's magnificent outing of himself with that pipe? Live on the Sunset Strip:

"C'mon over here witch."

I mean the way he personifies the pipe.

"Don't leave me alone witch. I'm lonely."

Oh god! What a fabulous... I worship that man!

DR: He was something.

LG: At least we have his words and voice and person on tape.

DR: Who would you say, I mean who feels that way about you?

LG: (Laughs) Well, I can answer it only because I was just given a piece of that when I read... from Off White up at Hue Man {Bookstore}in Harlem and one of my guest's is this wonderful younger journalist Michael Deibert who has just published a brilliant book abut Haiti called Notes from the Last Testament...

DR: My husband is Haitian.

LG: Did he grow up here or...

DR: He was born in Haiti and only lived there for two years.

LG: Well Michael is an American but he spent a lot of time in Haiti reporting for all sorts of news organizations and when we were at the party after my reading he said "I want you to know that Born Fi' Dead was one of the books that made me know I wanted to become a journalist." That was pretty wonderful - to know that book had meant something that deep.

You know I never think of myself as heroic. There are Jamaicans who have said to me that Born Fi' Dead was a tremendously important book for them because it was a permission grantor to name names and to talk in a journalistic way, not in a fictional way or a movie way or a reggae music way, all of which are arts, but talk in a journalistic fashion about the reality of political corruption in Jamaica and this horrible alliance between the politicians and the gunmen, to control the poorest of Jamaica's poor. That makes me very happy although I must say that I am still being sued by the Former Prime Minister so I don't know if I can recommend telling the truth on political truths because they will sue you.

DR: Well that clearly took a lot of courage. It doesn't sound like it was easy...

LG: It wasn't and I never really admitted to that because when I was writing Born Fi'Dead I had this horror of what a lot of people wanted me to make that book which was "Oh White woman does ghetto". Blahhhh. I mean...that was not what that book was. So therefore I consciously was always striving not to think of myself as being brave...Brave shmave. People who have really created this book by telling me there stories are living in this hell 24/7, 365. They are brave. I am just a witness. I'm just down here trying to get this on paper. But I think in retrospect it was much more dangerous than I recognize. I think that I woke up to that, not in Kingston Jamaica, but in Brooklyn.

One afternoon, when I was hanging in this crack house where I spent a great deal of time and knew a lot of the denizens, the cops broke in --plain clothes looking for guns. They kicked in the door with guns drawn. The only thing that gave them away as cops was...that they had bullet proof vests on. It took me about 15 seconds...to realize that these are "undercovers" and they are looking for guns and if so much as a car backfires on Roger's Avenue, they could open fire and...

But I think I was doing this, Dana, and this is all so unconscious, as a way, it was my way of paying my dues as I saw it, to a world that had been demonized by the white media and let's face it, because I was still then a drug user, it was my world. Now maybe I was white and might not have gone to prison for the same offenses that these people would have had they been busted - I knew that - but I think I was trying to be "down with them", and I admit to this even though it is hopelessly liberal...I think I was trying to sort of prove that I was with them in spirit. Ridiculous when I look back on it. This White woman of privilege hanging out on these street corners in Crown Heights trying to interview people. But I am not sorry I did it. And it may sound hopelessly liberal and It may be easy to make fun of it - I myself would make fun of it - but I think it was in many ways my swan song to a period in my life when I was a druggy and I was very confused about the fact that black people who used drugs were criminalized, white people quite often, got off scott free. There was some part of me that didn't want to get off. God knows I didn't want to go to Rikers. I am not that crazy but I at least wanted to get down there and bear witness and say "Look, I am like theses people. I am an addict too", which is a very strange impulse when I look back on it but,

I am not ashamed of it...

DR: I hear a lot of fearless-ness even though some of it also sounds like naiveté. What scares you most?

LG: For a long time I was afraid of my own feelings. That was one of the things that led me to take drugs. I was certainly terrified of loving and being loved. I was terrified of having children and never did and have deep, deep regrets at 56, that I missed that boat. I was afraid of things that I think - I don't want to say "normal people" 'cause what the heck does that mean - but things that people who have been loved and who are secure don't give a second thought to. They grow up, they marry, they have children, they make homes. They don't keep falling in love with married men or narcissistic unavailable cruel men. They find a good man and stay with them. I was terrified of all those things; those were really my deepest fears.

I think that I was, and still am, afraid of being misunderstood. It's been one of the hardest parts of working on Off White and walking that road to accept that I am going to be misunderstood because this is reality! Racism and the gulf between black and white is going to mean that, in my life, I am going to be viewed in certain ways at certain times and that's O.K. I can't control that. I think for a long time Dana, I really wanted to control how people of color saw me. I wanted to be loved. I wanted to be accepted. Now I think I am much more able to say "This is who I am."

..You wake up and say "Wait a minute. Why should people of color love me?!" Hello! This is a huge fact of life in America and in American history.

DR: What would you say that your biggest contribution is to the world right now?

LG: To go on writing. To go on fighting the terrible, terrible situation we are in in this country right now. I don't think I have made my biggest gift yet. I think it's ahead of me.

This wonderful reporter in Wilmington, North Carolina asked me on air if I had found myself yet. (Laughs). I looked at her and said "No", and she said "Well that's good because once you have, it's all over."

I think that my best work is still ahead of me. My real contribution is still ahead of me. I would like to say that before I go off this planet into the next dimension that I have really made a contribution toward dialogue between the races in this country. That would be my dream, to really be able to further and open up that dialogue. It's a funny thing because there is so much about life that I am very hopeless about. One of them tragically is the environment. I have terrible despair about mankind's ability to reverse the things we are doing that will make this glorious planet of ours not livable. Many people are very hopeful about environmental change and they might be the same people who look at me and say "How can you keep hope alive in the matter of racism in this country? How can you believe that it is possible to, if not eradicate this disease?"

I really think it is the worst disease of our planet. If you look at the bottom of everything you find racism - but I remain very hopeful. I know that has to do with how I was brought up and when I was brought up because I was brought up during the lifetime of Dr. {Martin Luther } King. I saw people change. I saw it with my own eyes and I'll never forget that. That hope for change is what I will tie in with my contribution to life, to history, to humanity. And if I could just change one person; the way they saw the world, I would be happy...

It's hard because in order to do it you have to risk and go out on a limb. When someone uses the "N" word you have to make them understand and not shame them. You can't humiliate people. You can't kick 'em. You have to educate and that's what's hard 'cause you get so angry. If you really want to change hearts, you have to go about it in another way.

DR: A hundred years from now, what do you want remembered for?

LG: My books and what they said, what they told about life, the love that was in them and what I tried to do to leave the world at least a little bit better than the way I found it. That is what everybody who has a social conscious always says. But that is what I would love to be remembered for.

I would love to be remembered for having made some kind of a difference. I'd also love to be remembered for having made a million dollars so I could endow a scholarship fund. I mean that's what I would really love to be remembered for!

Thanks Laurie!