David Turnley, Pulitzer Prize winning photojournalist and filmmaker

David Turnley (left) with his

twin brother, photographer

Peter Turnley

David Turnley is considered by many to be one of the best documentary photographers working today. Winner of the Pulitzer Prize, two World Press Photos of the Year, and the Robert Capa Award for Courage, he has photographed the human condition in some 75 countries around the world. Turnley was a Detroit Free Press staff photographer from 1980 to 1998. He was based in South Africa from 1985 to 1987, where he documented the country under Apartheid rule. He was based in Paris from 1987 to 1997, covering such events as the Persian Gulf War, revolutions in Eastern Europe, student uprisings in China and the disintegration of the Soviet Union. He has published seven books of his photographic work including his last "Mandela: In Times of Struggle and Triumph", from his extensive time over the last twenty five years photographing the evolution of South Africa, Nelson Mandela and his family. Turnley earned a B.A. in French Literature from the University of Michigan, received Honorary Doctoral degrees from the New School of Social Research in 1997, the University of St. Francis in 2003,  and has also studied at the Sorbonne in Paris. He studied filmmaking under a Nieman Foundation Fellowship at Harvard in 1997-1998. David has Directed and Produced three feature-length Documentaries. The Dalai Lama: At Home and in Exile, for CNN, nominated for an Emmy; La Tropical, called by Albert Maysles "the most sensual film ever shot in Cuba"; and his recently released, four year in the making, epic story of Shenandoah, located in the tough coal region of Pennsylvania. David is an Associate Professor at his alma mater, the University of Michigan, School of Art and Design, and The Residential College. The proud father of two children, David lives with his wife Rachel and family, in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

To be with David Turnley is to be in the presence of your own magnificence. It is my pleasure to know him. Enjoy what he has to share about himself and about his views.

DR: David, tell me anything that you want to about you, your life, your work...

DT: I was out in Indiana on Tuesday. I was receiving an award - The Indiana Governor's Award - so, when I received this, I had to say a few words in front of the Indiana Audience and of course it kind of took me back to my being raised in Indiana. And, I was trying to think about what things about my life, in relationship to anything that I may have accomplished, and what the inspiration might have been, in terms of arts and my work as a photo journalist...and yesterday I was walking down the street and I was realizing the extent to which the words "We are all created equal" had been such a part of my youth. That Dr. King's words really were in my family and in my era...I am 50...but you know, certainly specific to my family during that era...I was raised at the dinner table and that was really an important topic on life and yet, the reality certainly, in my hometown, did not play out that way. I mean, it was essentially a segregated town.

As an athlete - I was a pretty good football player. My teams, only starting in high school, were integrated. The schools previous to that, were segregated. And so, suddenly in high school, half of my team, at the end of a practice, would have to get on a bus and go back to the inner-city. Or, at the end of a game, after we had just come together in this solidarity, and felt that solidarity, and then suddenly you know, at the end of the whole thing, after we had put our clothes on in the locker room, they'd get on a bus or get in cars to go back to another part of town. And I knew that part of town because my parents, I am proud to say, were always very outspoken and active in their way, with civil rights in our city. So the words "We are all created equal", as much as they came to be for me, the essence of how I interact with the world, there was also a deep sense of injustice that I was witnessing.

I was thinking that the word dignity was sort of the...I had to, at some point process, "How are we created equal?" and "What is equal?", 'cause clearly things weren't equal. So what is it that we have that is equal? And I came to understand, pretty young, that what we all have available to us is -

Dignity.

When I fell into photography, it was then...the idea -- which came as a total surprise to me - the idea that I could use a camera to essentially pursue that mission which was to reveal this idea that everyone has innately some inherent dignity. So that's been kind of my mission. Whether it was in the beginning of my photographic journey in Fort Wayne, Indiana, or as I have gone out into the world, it's really been my own need to confirm this idea somehow.

DR: That everyone has dignity?

DT: Yeah. That the idea that "We are all created equal" somehow is a truth and how I could find that was to somehow seek...well, it's just always been about trying to seek that -- confirmation of that.

So, now I am fifty years old and I have certainly traveled all over the world. I have worked in about 75 countries and covered... I didn't set out to be a war photographer but...one could legitimately call me that, although I have tried to redirect my life quite a bit.

DR: What do you mean?

DT: I have, probably as much as anybody, witnessed the manifestation of conflict in our world, but I have to say, I think of myself as a very optimistic person. I think about that and what's that about and how do I maintain that, given what I have seen. The truth is that along the way, I have probably witnessed more acts of graciousness and generosity than anything else and that is what has imbued me with such a deep affirmation of our potential...that, I just can't let go of. If I lose that, I'm gone.

And I would have to say...I was lucky. I had parents who were madly in love for about 52 years and that also imbued me with a real sense of hopefulness about the ability for people to find respect in each other. But that is a long story though...

DR: You are very passionate. What are you most passionate about?

DT: Love.

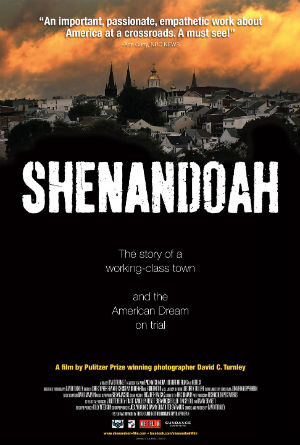

An epic feature documentary about a coal mining town with a fiery immigrant heritage, once pivotal in fueling America's industrial revolution and today in decline and struggling to survive and retain its identity, soul and values - all of which were dramatically challenged when four of the town's white, star football players were charged in the beating death of an undocumented Mexican immigrant named Luis Ramirez. Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer David Turnley's most personal work, SHENANDOAH creates a deeply felt portrait of a working class community, and the American Dream on trial.

Click here to view the trailer of David Turnley's SHENANDOAH.

DR: I can really get that about you. How does that inform your life; play out in your life?

DT: Well currently, I am involved with someone that is informing it quite deeply. I have found somebody recently that I am feeling a profound sense of respect for and just also someone who I am totally enamored with. And I do think that, yes, in sort of a lifetime pursuit to find that, having witnessed....

...what defines that for me is respect. We can put all of the flowery stuff into it, and attraction and all that, but I do think for me what defines ultimately the potential for real connection is --

Respect.

DR: And what do you respect?

DT: I respect people for who they are; people who are true to themselves, to their passions, to their convictions. I happen to believe in creativity as a value, as a virtue. I am always attracted to people who have found in themselves, the confidence to express themselves in whatever way that is.

DR: Yes. That is attractive. It really does make life interesting. Let me ask you - what are you interested in? What are you curious about?

DT: Hmmm. Well, I am always curious about people's life experiences and how they have come to be who they are. And, I suppose I am most often curious about people who I feel at some level, have experienced some adversity in their lives and I am curious about how they have coped with that.

DR: Yep, Me too. And why is that for you? Why are you curious about that, in particular?

DT: Well I think it's probably having realized pretty early that you could say against the backdrop of this concept that "We are all created equal" that life, as it manifests, is not necessarily always fair. So then the question is, "How do people deal with that?" And I have certainly witnessed people who have dealt with that in the most unbelievably self determined ways and not to mention, so often in such gracious ways. I am very intrigued by the concept of grace and where that comes from.

DR: And grace for you...Can you describe what that is, what grace is for you?

DT: I think it can be a lot of things, Dana. I mean certainly I am very visual in my sensibilities. I see grace in an aesthetic way; as simply as how someone puts themselves together. But I think more profoundly for me, it's more about how someone reveals their soul.

DR: Yes. It's so interesting that you are mentioning things that I have been contemplating a lot lately. For instance I have, lately been extremely curious about people and who they become as a result of their adversity and how they take adversity and use it to move forward in their lives.

DT: Absolutely.

DR: And, I don't know, I have found that some of the most beautiful people have had to struggle through something to get to where they are and they are some of the most interesting people too...

DT: I totally agree with you...

DR: ...but enough about me (laughing) and what I think....

DT: ...(laughing) I think we share a lot in common...

DR: ...tell me, tell me, tell me about a time in your life when you had to deal with adversity and then turned it around somehow.

DT: Well, I think the first time, professionally, I felt a coming together of what I might have, in terms of my own human assets; my trying to make a contribution in a constructive way, was in South Africa in the mid '80's.

I had gone there at a time when apartheid was certainly a household concept in this country in terms of a kind of general pervasive sense of that injustice...but also...I didn't feel so different in my own hometown. You know there was a kind of apartheid in Fort Wayne, Indiana, that I felt very profoundly. So, when I got to South Africa, in 1985, as much as the word and the legislative system of racial segregation had been perfected in South Africa, it wasn't unfamiliar to me. It felt very familiar. So I was able to go at that from a perspective of, I think, empathy. And that, pretty quickly, I understood to be, the most profound approach to the issue. That what I could accomplish was more profound in trying to reveal the humanity of South Africans and how they interact, as opposed to necessarily trying to pound with a hammer, the idea that there was one group that was good or bad or... you know...I really kind of wanted to, well it wasn't that I wanted to, it was that I felt a palette of humanity, not a palette of color. I felt that everybody had been victimized by this system. And, quite honestly, I felt that growing up in this country. I continue to feel it.

DR: So everybody on both sides of the condition...

DT: Whatever gets in the way of people connecting as human beings, just always seems to me to be a major tragedy.

DR: It's like we have all inherited that condition to some degree.

DT: Absolutely. During those three years that I worked there, and I worked very intensively, I felt like I was able to do my work. It got published all over the world. I was able to make a fairly valuable contribution so, I was very proud of that. And what I found was that I had the ability...that what I bring to my work is that I lose consciousness of my exterior when I am with people so that I am able to very quickly integrate in any group of people. That can be very disarming and it earns me access into people's lives.

DR: Kind of like the quiet observer?

DT: Well I think it's that if you look into someone's eyes and you are open, people feel that. So the rest kind of gets lost very quickly. You sort of find a very disarming connection that defies the exterior.

DR: And you know, that is exactly how I experience you.

DT: Well, likewise.

DR: I can speak first hand about your ability to do that. How would you define then, your overall contribution to the world?

DT: I question that quite often, to be quite honest. I don't feel at all smug about my contribution. In fact, if anything, I am very hard on myself. I would like to think that the work that I have done as a photographer, touches people at a very soulful place and very quickly people get moved beyond the exoticism of diversity; witnessing human life in a way that they can touch. Then I'd like to think that I look at the world with eyes and with a heart that is not only hopeful, but fun at some level. For me that is my driving force.

DR: Really?

DT: Yes. I like to dance for instance.

DR: What kind of dance?

DT: Anything. I just love to move to music.

DR: Yes?

DT: That is available to all of us... it doesn't take a lot to get me excited. I mean I can have fun doing very simple little things - including sitting here looking into your beautiful eyes....

(I laugh because I am now -- really disarmed and so I ask the first question that comes to mind before my blushing becomes obvious)

DR: Um, so if I were to ask you what scares you and how do you overcome that, what would you say?

DT: That is a creative question. I confront pretty quickly and readily, fears that other people may not. I can make pretty cautious and calculated decisions about risk when it comes to going to war zones and how I might deal with that. I kind of figure out what is manageable and what isn't and what I think I can....I think probably my biggest fear is my insecurities -- not danger.

DR: And isn't that such a human quality?

DT: Yeah. Like sometimes I am in the city of New York and I think to myself

"If I can eradicate my insecurities, the palette of interesting humanity is infinite. It's just there."

So the only thing getting in the way of my intersecting with that is me.

DR: So just share with me one of your insecurities.

DT: My own prejudice. Allowing my own prejudices -- that I have been formed with -- to interfere with my giving someone a fair chance, and giving them a fair chance about me...it is precisely what I am advocating, that I remove the reflexes that might get in the way of what otherwise could be an interesting connection. Whether it's because of my own...

It's interesting. I grew up in a liberal family with a very acute sense of the disenfranchised. I can't honestly say that there is any reason why I should have ever felt disenfranchised. But for some reason I deeply identify with the disenfranchised. One of the challenges that I have sometimes is, that if I encounter someone who projects whatever the opposite of that is - privilege - I have to work at not allowing that perception to get in the way of my simply giving that encounter a fair chance...

DR: So when that comes up, how do you overcome that?

DT: I have to work at it. I really do. The way I overcome it is to realize that I would be the victim of that because it would only serve to create a very narrow range of human beings that I would interact with. And, at some level, that's a very sad way to live. You just limit yourself...

DR: I don't know, I think that you get to a certain point in life... I get really horrified when I think about what I have potentially missed out on in life because I made up my mind about someone or something too soon...

DT: That's right.

DR: ...and as I am expanding my capacity to accept things or be more curious, the things that I am finding out about people and things are so fascinating. And I think "Oh my gosh! What have I been doing!"

DT: Right.

DR: I think that when we can notice ourselves getting in our own way, it opens a door.

Tell me what makes you happy.

DT: Well children make me happy. My son makes me very happy. All of the qualities of youthfulness, an openness to life... I love dance and rhythm. It could be music but it could also be anything that I ...anecdotes to people's lives. It can be what I witness with my eyes....

Honest people make me happy - always. People who are just who they are, unabashedly, that makes me happy....Sharing in other people's life experiences, even when those experiences aren't happy, that makes me happy...A sense of connection of my life to other people's lives...I think the thing that probably makes me unhappy is isolation or a sense of isolation, although I can enjoy being alone. The woman that I am with right now makes me happy in a way that I have never experienced. It's a kind of pure joy. In the morning when I see her smile, that makes me happy.

DR: The fact that what you are passionate about is love, the fact that, what makes you happy is people and the woman that you love - well that is so consistent with who you are; so simple and so beautiful.

The last question that I want to ask you is -

A hundred years from now, what do you want to be remembered for?

DT: Having been a good father, and having had the capacity to make someone's life happy.

DR: Anything else?

DT: Nope. That more than anything else...

Thanks David!

McClellan Street

More than 100 black-and-white images of a working-class neighborhood in Fort Wayne, Indiana, in the 1970s grace the pages of this photo-essay produced by acclaimed photographers David and Peter Turnley. These hauntingly beautiful, raw and real photographs documenting life on McClellan Street were taken by the Turnley twins with a single camera as a high-school project. Although the brothers did not grow up on McClellan Street, their photographs represent a very personal, sincere, direct, and loving interaction with life on a street in the heartland of America. Many of the McClellan Street residents had migrated from Appalachia and some were of Hispanic origin. In a neighborhood that many might have ignored, the young Turnleys saw beauty, diversity, and wonderment. With a maturity beyond their years, they captured the life of this community for future generations.