Author and Eco-Activist, Paul Hawken

Paul Hawken is an environmentalist, entrepreneur, journalist and author who has dedicated his life to improving the relationship between business and the environment, and between human beings and living systems in order to create a more just and sustainable world.

Keynote Address: 2004 PASA Conference

Paul Hawken, of Smith & Hawken and Erewhon fame, addresses Pennsylvania Association for Sustainable Agriculture.

Thank you very much for welcoming me. I'm not wearing a suit so you don't mistake me for a businessman.

I don't know about you, but I didn't sleep well last night. I thought a lot about what Percy [Schmeiser] said last night, and I was thinking about my grandfather and what he would have done if somebody walked onto his fields. It was always locked and loaded. Just listening to Percy made me angry … and it wasn't even my farm.

As Percy did last night, I'd like to just give you a little bit of my own background. I grew up mostly on but sometimes off the farm. It was my grandfather's, in the San Joaquin Valley. He'd been a farmer since the '20s and through the depression. He always had two jobs, one off the farm and one on. You probably know that story.

We were Scotch and German and Swedish and Cornish on that side, and on my grandmother's side we married into Portuguese and my favorite uncle was Portuguese, Joe Kreitz. He grew olives. I tell this story because it made a very big impression on me. He was really happy one day when he got a big contract to pack olives with Safeway. It seemed like, boy, the gravy train had rolled right in. Every year Safeway bought a few more olives, or quite a few more, and every year they just negotiated that price down just a little bit less and pretty soon it got to the point where they were most of his business and he wasn't making any money and they wanted a lower price again.

I remember being a small child going to his place near Corning, and there were trucks there and everyone was upset and, basically, he had gone bankrupt with Safeway, and it left a very deep impression on me about the relationship between farming and corporations.

At the same time as I grew up, I was pretty sick. I had asthma and that had a lot to do with the fact that I grew up in the San Joaquin Valley which has, along with the Bronx, the highest rate of asthma in the United States. One out of five children carries an inhaler in the San Joaquin Valley. When I was twenty years old I got tired of taking medicine and I thought, well, there must be something I can do about it, so I started reading books from Rodale and many others. And it basically said "Clean up your act. It might have something to do with what you're eating."

"I got rid of the hamburgers, the shakes, you know, the French fries, which I missed dearly. And sure enough my symptoms went away. And then I went back to eating the junk food and the coca cola and, boom, it came right back.

It went back and forth until I was finally convinced that food made a big difference in my life."

So, I started to eat pure foods, natural foods, which wasn't so difficult because it was the food that my grandmother canned and froze and served and baked - so it wasn't a real stretch. I changed my diet very radically. I got rid of the hamburgers, the shakes, you know, the French fries, which I missed dearly. And sure enough my symptoms went away. And then I went back to eating the junk food and the coca cola and, boom, it came right back. It went back and forth until I was finally convinced that food made a big difference in my life.

I noticed in the process that it was difficult for me to get food. I was living in the Bay area at the time, and had to go to this Lebanese store, to this Chinese store, to the Japanese store, to this place where they had wheat, etc. I just thought that somebody ought to put it all together in one location. That was how in 1966 I started what was one of the first of what I call natural food stores, which is basically a farm stand in the city-a store that did not sell vitamins at all. We sold food.

I knew nothing about business. I was just stunningly naïve. [This was in Boston, where Paul moved in the mid-60s. The business? Erewhon.] I remember going to Harvard, sneaking into classes, listening to time sequence matrices of progress analyses, using the BCG model of cows and dogs, and I'd be taking notes and go back to my warehouse and we're selling … wheat. I could never figure out how to apply it.

I remember in a coffee shop there listening to two guys talking. I was twenty, but I was thirteen when it came to business. My only prior commercial experience had been a paper route. These two guys were talking, Harry was talking to Manny and Manny was saying to Harry, "Geez, I'm really sorry about the fire at your warehouse last night," and Harry said, "Shhh, it's tomorrow night." It's a little different than the inventory control methods they were teaching at Harvard.

But we grew and we grew. By the time I left seven years later we had 50,000 acres of farmland under contract in the United States that was all organically or biodynamically grown. And remember this was the late Sixties. We had hard red winter wheat from Montana, hard red spring wheat from Texas, we had durham in soft white wheat from eastern Washington, we had buckwheat from Pennsylvania, we had long grain rice from Louisiana, medium grain rice from Arkansas, we had cocoa from California, open pollinated sunflower seeds from North Dakota, and so on and so on and so on. We had vegetables, fruits, beans, and nuts.

What I decided to do was recreate a food supply. The reason I did that was because when I first opened up and started selling things, somebody came into the store and they held up a bottle of Hain cold pressed oil and they said, "How do you know it's cold pressed?" I said, "Well, it says so." I defended it until they left, and then I thought about it and I said to myself, "I don't know a darn thing about the food I'm selling." So I wrote a letter to Hain. It said, "Would you please provide me a letter attesting that your oil is cold pressed." They came back to me and said, 'Well, it's not really cold pressed. It's cold processed, which means that once it's extracted,we freeze it and draw out the stearates and …." So I started writing to other manufacturers and I found out that virtually everything I was selling was a fraud. This was stuff in health food stores.

That's why, in our stores, it was the name of the farmer, the name of his farm or her farm, the name of the agricultural practices used, the type of soil--it was completely transparent so that we didn't have to ask you to trust us. We started the first certification organization in the United States, in California, as well. That's my background with farming.

"When I first opened up and started selling things, somebody came into the store and they held up a bottle of Hain cold pressed oil and they said, "How do you know it's cold pressed?" I said, "Well, it says so."

I defended it until they left, and then I thought about it and I said to myself, "I don't know a darn thing about the food I'm selling.""

Since then, I have always worked in my life in this relationship with business and the environment because, going back to my Uncle Kreitz, you can see that business has the power to destroy or it has the power to restore. It can be at service to farmers, to the land, to consumers, or it can be something that takes advantage of the land, of the environment, of consumers. Generally speaking and almost universally, in my experience, the bigger the company gets the less likely it is to serve humankind.

Now, it's interesting to talk about sustainability. Recently I was asked by a California group to talk about sustainability, and one of the sponsors said she didn't want me to speak unless there was somebody there to present the other side. At first I was upset, but then I got pretty excited about it. I would love to hear the other side. I am dying to know what the other side of sustainability is. Some even make the business case for it as well. What is the business case for being the last generation on earth? That's interesting. The business case for double-glazing the planet with the carboniferous period? I'd like to see a Harvard case study on that. And what's the business case for an economic system that tells us it's cheaper to destroy the Earth than to take care of it in real time? I want someone to explain to me why we are given economic signals that are deeply, deeply antithetical to our own deeply held values and common sense. Why do these innate qualities of goodness, of inclusion, of generosity get thwarted consistently by commerce and politics? In short, why is it that we live in two worlds instead of one? I want to know. And that person never showed up.

It's often said that talk is cheap, that conversations are not. This conversation you've been having [at PASA] for the last thirteen years now? First of all, you know it's not cheap. The organizers know that. It takes a lot of money and organization and sweat to do this. But these conversations are occurring around the world. There are conversations about ecology, about justice, about democracy. The concept of justice is not just about rights and wrongs. At the heart of this conversation about sustainability, it's really about the language of kinship. It's a language of possibility. It's not the language of foreclosure or exclusion or retrogression.

It's the language of possibility, particularly for those people who have been exploited or ignored. To have this conversation it requires that we listen patiently and carefully to each other, of course, but even to those whose views we many not agree with. And all of us carry that responsibility--to carry this conversation forward into the world about what it means to be a human being at a time when every living system on Earth is in decline and the rate of decline is accelerating.

In some ways that's putting it just a bit too polite. In fact, life is being annihilated on earth. There was on March 7th, 2000, in Nature, an article about extinction, recovery, and biodiversity. It said this: "It takes the Earth ten million years to recover from a mass extinction of species, far longer than previously thought. It takes the environment just as long to recover from the extinction of even just a few species--smaller events that nevertheless rip holes in the biosphere that are impossible ever fully to repair. When you lose a species it's not ever coming back. You can't recreate an animal - extinction is final."

The article, by Kerchner at UC Berkeley, predicted that up to half of all species would vanish over the next 50 to 100 years. "If we deplete the planet's biodiversity, we will not only leave a biologically impoverished planet, not only for our children or our children's children, but for all of the children of our species that there will ever be." It may sound a little neat, a little pat, but it cannot be embroidered. The fact is that the corporate form of commerce that has been practiced on this planet is destroying life on Earth.

And the marginalization of nature is always the marginalization of human beings. Always. They do not occur separately. It was Lewis who said that man's power over nature turns out to be the power exercised by some men over other men with nature as its instrument. It is the power of corporations over people and place. It is the power that was never granted and must be taken away by those to whom this power rightly rests.

Today, the fluency with which we describe our relationship to life also has been debased. The environmental and social justice movement is an attempt to, in a sense, enlarge its vocabulary to create a vastly expanded sense of what is possible for human kind. Fendera said that the struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting, but it's also the struggle of language itself against what has been muted, of intelligence and insight against the confinement of the tellers and sound byte, of human decency against the convoluted lies of corporate communications offices.

"I want someone to explain to me why we are given economic signals that are deeply, deeply antithetical to our own deeply held values and common sense. Why do these innate qualities of goodness, of inclusion, of generosity get thwarted consistently by commerce and politics?

In short, why is it that we live in two worlds instead of one? I want to know. And that person never showed up."

Our grief over the loss of lives in 9/11 was manipulated to justify war. Our love of nature is being manipulated by corporations to continue their predation of the environment and our people. The media is so concentrated in this country that we are simply breathing our own exhaust fumes. At some point, in the face of remote tyranny, as is in the face of corporate hegemony, you have to do something. As the poet Rumi wrote, just don't stand there and pray - do something. Each generation carries with it a story, you know, and then it passes on to the next generation. The present story is the endless extension of industrialism, of toxicity, of combustion, of exploitation. Industrialism and industrial farming took a complex living system and transformed it into a low life high way system. And we are told that this system, which describes people as easily as it describes ecological integrity, is the cheapest, and that social justice, living wages, local democratic rule, green buildings, global food security, renewable energy and biologically based agriculture are just too darn expensive. At our best we are asked to entrust these goals to transnational corporations and free markets. We are literally told that it is cheaper to destroy the Earth in real time rather than to conserve and honor and maintain the dignity of humanity and this miracle that we call life. So, at the heart of our current system is the belief that life is expensive. This is of course bizarre, it's upside down and backwards, but it goes back to language and perception.

In my work I get the opportunity to stand here and look at people like you many, many times--maybe 600 times now, I've given a keynote speech in this country and countries around the world. And what I have come fiercely to believe is that this world lies in the hands of ordinary people … and thank God. Here's what I mean by that: It is just simply not realistic to expect or look for courageous and inspiring leadership from any large institution, whether it be scientific, academic, business, or government. I do not mean that institutions are unnecessary but the scope and breadth of the world's problems now lie far beyond the reach and the ethos of these monolithic organizations that have basically trailed us into the 21st century.

The real questions are these: Do people have the right to determine their own biological destiny? Do they have the right to live in their homes secure from corporate and government oppression? Yeah. We fought the British to overthrow the yoke of external domination; we certainly do. So it's a completely rhetorical question. We have an enshrined right to live without the threat of remote tyranny and we have the right to resist it. It is the backbone of this country. It was the right of the First People who proceeded us (to be trampled on), but it is definitely still our right as well.

Thus, the answer to agribusiness cannot come from Washington D.C., it cannot come from Philadelphia. It must come from bioregions. Life is regional. It's not national, you know. If we had a real government in Washington D.C., I would still maintain this position. Given that we only have a simulacrum of a government, it becomes imperative to seek local control. Not only is all politics local but, really, so is all sustainability.

Now, we hear around the world this cry against globalization. And I would like to, in a sense, offer you the idea that this cry against globalization is the same concern as you have, and it's a protest against corporatization of the commons. It is so insidious because the corporations that are issuing social responsibility reports are busy closing and dominating the world's commons. These "commons" include our stories, which are our culture. They include our music, our right to determine our own destiny, democracy itself. They include the ability of people to decide what is and what isn't acceptable in a locale, a region or place. All these areas in our life are being corrupted by corporations and as Wendell Berry would tell you, all publicly held corporations live a lie. They believe that we reside in a world where capital has the right to grow, and that that right is higher than the rights of people, of culture, of place, of those qualities that have historically been our commons.

There's something colossally wrong with this view. You can't get to sustainability from an economic model that strives to increase the amount of money large corporations have. You can't get there if you're destroying small local economies. You can't get there if you're McDonald's and you're spending two billion dollars a year to get our children to eat junk food. We cannot correct environmental problems if we don't correct the assumptions that cause them. Most of the world's government and economy are under the control of corporations, and corporations are striving to increase this control. Yet the world is increasingly out of control. There is a direct connection between these two phenomena.

A highly placed government official from the Clinton administration met with his counterpart in the Bush administration. His conclusion? "They are not governing. They are preventing governance in order to serve their masters' corporations."

Even if a large corporation does not engage in that activity, why are they mute in the face of this liquidation sale of our commons to private interests? This weight of corporate colonization is having disastrous results in San Francisco, Suez, Lanais, in France. Novartis, Dupont, Monsanto want to take control of-and this is a direct quote in a private meeting-"ninety percent of the germ plasm of ninety percent of the caloric intake of the world." That's their corporate strategic goal. Now, these are companies who made their money making toxic aniline dyes, animal hormones, artificial sweeteners, explosives, and pesticides.

"They can get out of our schools, they can get out of our stomachs, they can get out of our government, they can get out of our rivers, our oceans and our forests, they can get out of our skies and our soils and get out of our farms, they can get out of our seeds and human genome and they can stop molesting our children.

That's something corporations can do positively."

Ted Turner said there will be two media companies in the world. He wants to have a stake in one of them, AOL/Time Warner. Rupert Murdock agrees and wants to be the other. McDonald's opens up 2,800 restaurants a year and even the U.S. government has said that the doubling of childhood obesity and diabetes in the past ten years in due to fast food. Right now one out of every five meals in the U.S. is fast food. McDonald's wants that to be true everywhere. Coke has now achieved 10% of the world's TLI (Total Liquid Intake). Ten percent of anything you drink in the world is sold to you by Coca Cola. Their goal is to go to 20%. What do you think their goal will be at 20%? These are absurd and devastating goals for corporations.

Somebody asked me once, "Well, can't you say something positive?" So I will. There are some positive things that corporations can do. Let me list them to you:

They can get out of our schools, they can get out of our stomachs, they can get out of our government, they can get out of our rivers, our oceans and our forests, they can get out of our skies and our soils and get out of our farms, they can get out of our seeds and human genome and they can stop molesting our children. That's something corporations can do positively.

Here's another Wendell Berry quote: "A corporation does not age. It does not arrive as most persons do in realization of the shortness and smallness of human life. It does not come to see the future as a lifetime of the children and the grandchildren of anybody in particular. It can experience no personal hope or remorse. No change of heart. It cannot humble itself. It goes about it's business as if it were immortal with the single purpose of becoming a bigger pile of money." And I believe that until corporations understand that they are spearheading a kind of commercial fascism, they're going to find that our resistance will continue to grow and grow.

I say fascist because it's fascist when there's an assumption that a small group of people know better than the larger group. That is called fascism. It doesn't matter that it's hard for us to use that word in our culture because we think we're a democracy. In The Latches in the Olive Tree, Tom Freedman wrote, 'The hidden hand in the market will never work without a hidden fist. McDonald's cannot flourish without McDonald Douglass. It is the hidden fist that keeps the world safe in the Silicon Valley." This is so bizarre that it is accepted as foreign policy.

The question to be grappled with by all of us is the shape of relationships. This is what this conversation of sustainability is about. What is going to be the relationship between a region and its people? Between companies, markets, and the commons which support all life. And we'll have to come down in the end to some very simple questions. Do we want democracy and self-determination? Or, do we want oligarchic institutions? Do we want a world of uniformity where the road from every airport to every city center looks like every other strip mall and every other part of the world? Do we want the world envisioned by Monsanto and Walmart and Disney? Do we want our nine-year-old girls being lured to McDonald's with Happy Meals and dolls? Or, do we want strong regional cultures proud of their heritage devoted to the land, committed to real development and the future of their children?

In short, do we want a world structured by mostly rich men or a world which is an expression of the fabulous qualities of human beings. That is what we're faced with.

We know that the way to create healthy, vibrant economies and societies is through diversity. There's no question about that. We know that scientifically. Any system that loses its diversity loses its resiliency and is more subject to sudden shocks and changes from which it cannot recover. This corporatization of the commons is the abject loss of diversity. It forces uniformity upon people, upon place. Historian Arnold Toynby said that the sign of a civilization in decay is the institution of uniformity and the lack of diversity.

So we can judge our companies now not necessarily by whether they're large or small, but by this criteria: the degree to which a company honors and allows diversity to emerge from a place, a country, a locale is a good thing; the degree to which it tries to enforce a one size fits all formulate solution to diet or media or agriculture I, in my opinion, going to be seen in hind sight as just as much of a criminal act as the deracination and the slaughter of indigenous people by the Spaniards, and later by us. We will look back at what we're doing now and see it as a violation of humanity. I believe that in our lifetime we will convict corporations of crimes against humanity.

We know-you know in this room-how to transform this world. We know what to do. We know how to provide meaningful, dignified living wage jobs for all who seek them, how to feed, clothe, and house every person on Earth. What we don't know, admittedly, is how to remove those in power whose ignorance of biology is matched only by their indifference.

This is a political issue. It is not an ecological problem. But the way to save the Earth is to focus on its people and in particular those people who have paid and continue to pay the highest price under its current system. They are women, they are children, they are communities of color, and they are the localized poor. This sustainability movement--without forsaking its understanding of living systems, of resource flow, of conservation biology--must move from a resource flow model of saving the Earth to a model based on human rights, the rights to food, the rights to livelihood, the rights to culture, the rights to community, and the rights to self-sufficiency.

Essentially, the sustainability movement must become a civil rights and human rights movement. Sustainability for me represents and stands for improving the quality of life for all people on Earth. Diversity means possibilities and choice, and the only kind of sustainable development that makes sense is about alleviating the suffering and honoring all forms of life. The world is waiting for answers, and right now the main providers seem to be fundamentalists--whether they be political or religious or economic. It was David Bower who said that environmentalists make terrible neighbors but great ancestors. There are two voices on the world stage and one is the voice of the wealthy and the other voice is the rest of us. One is a minority and one is the majority.

André Gide said once that one does not discover new lands without consenting to lose sight of the shore for a very long time. We are in deed in a very long period of this continuity from one system to the next. We do not know what it will be called. We do not know what it will be named, but we know collectively that we are moving towards it. We live in an extraordinary time, the most corrupt period since reconstruction.

"This shared understanding is arising spontaneously from different economic sectors, from every country in the world, from different regions and cohorts. It is spreading and growing worldwide. No one started this world view. No one is in charge of it and there is no orthodoxy.

This is the sustainability movement. This is what you are creating. It is the fastest growing movement in the world and it will prevail, not as an ideology but as a standard set by humanity for itself."

Nobody really talks about it, keep in mind. This is the president, the person you are sending into office with a criminal record. We can forgive that. But he appointed more convicted criminals than anybody in U.S. history and that should raise some eyebrows. He presided over the biggest energy crisis in U.S. history, and refused to intervene when the corruption was revealed. He appointed the richest cabinet in history of any U.S. administration. The poorest multimillionaire, Liza Rice, has a Chevron oil tanker named after her. He presided over the biggest stock market fraud in any market in any country in the history of the world. He created the largest government department bureaucracy in the history of the United States. I could go on and on.

The thing is, we live in very disturbing times. Mark Twain said that you can't see if your imagination is out of focus--and it's very hard to focus our imagination when what we see is a kind of shortsightedness and venality all around us. It has poisoned us, but we don't want to find ourselves at the end or our life wondering if we had made or done something particular or real, or in fact were simply merely visitors to the planet. There's this great quote. See if you can guess who said it: "This is not a time of gentleness, of tinted beginnings that's stealing to life with soft apologies. This is a time for a loud voice, open speech, fearless thinking, a time for all that is robust, vehement and bold, a time radiant with new ideals, new hopes of true democracy. I am a child of my generation. I rejoice that I live in such splendidly disturbing times." That's Helen Keller. Isn't it wonderful?

Remember. I said there were two worlds and two voices. In February, the New York Times said that there are two superpowers in the world, and one of course is the U.S. The other superpower is civil society. You are civil society. There are in the world today over one hundred thousand non-governmental organizations, foundations, citizen-based organizations, that are addressing these issues of social and ecological sustainability. They address such a broad range of issues: environmental justice, ecological design, affordable housing, conservation, women's rights and health, population, renewable energy, corporate reform labor rights, climate change, trade rules, sustainable cities, water, and more. Some groups conform, resist; others create new structures, patterns, and means; some do both.

What is so extraordinary about the time you live in is if you ask each of these groups, if you ask PASA, all of you collectively, the board, staff, and you ask these groups for their principles, their frameworks, their conventions, their mental models, their declarations, what is it that informs you? What is your mission? And we'll find that none of these conflict, amongst these 100,000 groups in the world. They don't conflict, but they are not the same. This is real human evolution. Such an upwelling of shared wisdom and understanding has never before happened in history, never.

In the past, movements have always started with the very centralized set of ideas and then dispersed outward from that - Christianity, Marxism, Freud, you name it--and generally became divisive over time. The sustainability movement does not agree on everything, nor should it ever, but it shares a basic set of fundamental understandings about the Earth, how it functions, the necessary of fairness and equity for all people in partaking of the Earth's life giving systems. All believe that their right to self-sufficiency is a basic human right. They believe that water, air, and oceans and land are sacred. That's God's business, not ours. But they do belong to us all in a sense that we are stewards of them. They do believe that seeds cannot be patented or owned nor can any other life forms by corporations. And they believe that nature is the basis of true prosperity and must be honored. That must we fight poverty, and not the poor.

This shared understanding is arising spontaneously from different economic sectors, from every country in the world, from different regions and cohorts. It is spreading and growing worldwide. No one started this world view. No one is in charge of it and there is no orthodoxy. This is the sustainability movement. This is what you are creating. It is the fastest growing movement in the world and it will prevail, not as an ideology but as a standard set by humanity for itself.

Now, it is said that society honors living conformists and dead troublemakers. So let's cast our lot with those who age after age with no extraordinary power choose to reconstitute the world, in Adrianne Rich's words. Some of you, I think--perhaps all of you--know Terri 'Tempest' Williams, the author of Refuge. Extraordinary woman. I was emailing her the other day actually about PASA, about this conference, about speaking, what it means to leave your home far away and go speak to people you don't know and go back home. We were just trading notes and I would like to close and read you what she wrote, because it's to you.

She said, 'I have been reading Emerson's speeches. They are revelatory. Ten thousand people would come to hear him speak. This is part of the American tradition. We pay a price, all of us, and each takes their turn. To PASA: Please don't lose heart. You each and all are courageous and revolutionary. We must support and build each other up. A crisis of confidence each of us faces in our darkest hours is only what the opposition wants. I have been reading Walt Whitman. We need his reminders, conscience, moral judgments, and justice. If something happens that we can no longer hear our voice, believe me: Your voice is loud, it is clear, it is resonant.'

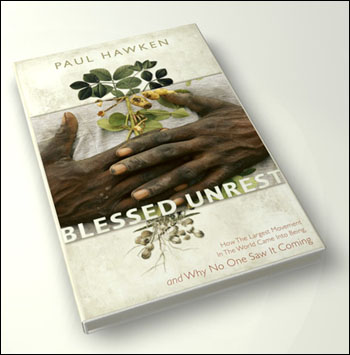

BLESSED UNREST: How the Largest Movement in the World Came into Being and Why No One Saw It Coming

Book Description:

One of the world's most influential environmentalists reveals a worldwide grassroots movement of hope and humanity

Blessed Unrest tells the story of a worldwide movement that is largely unseen by politicians or the media. Hawken, an environmentalist and author, has spent more than a decade researching organizations dedicated to restoring the environment and fostering social justice. From billion-dollar nonprofits to single-person causes, these organizations collectively comprise the largest movement on earth. This is a movement that has no name, leader, or location, but is in every city, town, and culture. It is organizing from the bottom up and is emerging as an extraordinary and creative expression of people's needs worldwide.

Blessed Unrest explores the diversity of this movement, its brilliant ideas, innovative strategies, and centuries-old history. The culmination of Hawken's many years of leadership in these fields, it will inspire, surprise, and delight anyone who is worried about the direction the modern world is headed. Blessed Unrest is a description of humanity's collective genius and the unstoppable movement to re-imagine our relationship to the environment and one another. Like Hawken's previous books, Blessed Unrest will become a classic in its field— a touchstone for anyone concerned about our future.Click here to learn to learn more about Paul Hawken's book, Blessed Unrest