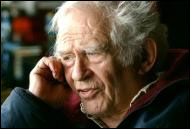

Thoughts from a Literary Giant - The Late Great Norman Mailer

Norman Mailer passed away on Saturday, November 10th, 2007. The world collectively mourns the passing of a great writer, a controversial pop icon and a talent that will be nearly impossible to replace.

"Mailer is forever shouting at us that he is about to tell us something we must know or has just told us something revelatory and we failed to hear him or that he will, God grant his poor abused brain and body just one more chance, get through to us so that we will know. Each time he speaks he must become more bold, more loud, put on brighter motley and shake more foolish bells. Yet of all my contemporaries I retain the greatest affection for Norman as a force and as an artist. He is a man whose faults, though many, add to rather than subtract from the sum of his natural achievements." -- Gore Vidal

Norman Mailer speaks out on the literary greats:

NORMAN MAILER, THE WRITER AS WRITER

By Hillel Italie

NEW YORK (AP) — His friends all tell similar stories: Norman Mailer at a dinner party, awards ceremony or afternoon gathering, hobbling on canes up or down a few steps or a flight of stairs, short of breath, as if getting from one place to another was a struggle even greater than finding the right word to finish a paragraph. Then, he would be seated, and was himself again.

"We would talk about everything," novelist William Kennedy said of Mailer, who died Saturday at age 84 after spending more than two months in and out of hospitals. "He knew he wasn't going to live very much longer, but he would still talk of taking on the greatest subjects. He always was working on something."

"He was absolutely dauntless," said Jason Epstein, who edited several of Mailer's books at Random House. "He was quite weak in the end, but he still planned to write a seven-volume novel about Hitler."

The Pulitzer-Prize winning Mailer, the eminent literary journalist, drama king and gentleman, eternal striver for the Great American Novel, seemed to embody in recent years not just one writer, but a generation for whom the printed word was a noble and endangered way of life.

More than such peers as Gore Vidal, William Styron or Kurt Vonnegut, Mailer was the writer as Writer, not a career to be printed on a business card, but a calling, an identity, with all the follies and privileges to which a man alert to his own gifts felt entitled.

He wrote letters to the president, sounded off on talk shows, likened himself to Picasso, placed himself on a "plateau" with Jacqueline Kennedy.

"Some part of me knew that I had more emotion than most," Mailer, who married six times and stabbed one of his wives, once wrote. He cautioned himself not to "exhaust the emotions of others."

"He was interesting, because he was interested," said Vidal, a longtime friend and occasional rival. "He had a radical imagination, a way of approaching subjects that was never boring."

"He was by nature bound to a style of excess," said E.L. Doctorow, who worked with Mailer in the 1960s as an editor at the Dial Press. "There were times when you would be fed up with him, but if you could conceive of American culture of the past 50 years without Norman Mailer, you would find it a lot drearier."

Lightning struck early for Mailer, and he struck back. In his 20s, he was the prodigy behind "The Naked and the Dead," the World War II novel that made him instantly, and prematurely famous. He came back in his 30s as the master self-advertiser, the anointer of John F. Kennedy as "Superman" at the supermarket. In his 40s, he was the fighting narrator-participant in "The Armies of the Night"; in his 50s, the cool chronicler of killer Gary Gilmore.

His hero was the authentic, autonomous man — the boxer, or graffiti artist, or maestro of jazz, or the "Norman Mailer" who starred in "The Armies of the Night" and other works of journalism. The bureaucratic mind was his enemy, from the military leaders of "The Naked and the Dead" to the Kleenex box-like skyscrapers that appalled him when looking out from his Brooklyn town house, to the processed presidency of Richard Nixon.

"Nixon's crime is his inability to rise above the admiration for the corporation," Mailer wrote in 1974, commenting on the Oval Office tapes that would help drive Nixon from office.

"Throughout the transcripts, he is acting like the good, tough, even-minded, cool-tempered, and tastefully foul-mouth president of a huge corporation — an automobile man, let us say, who has just discovered that his good assistants have somehow, God knows how, allowed more than a trace of tin to get into the molybdenum."

It was easy to make fun of Mailer, with his chesty and sometimes foolish pronouncements, his nerve as a man in his 80s to write a 450-page novel about the childhood of Hitler, as told by an underling of Satan, with a bibliography citing Milton, Tolstoy and Freud.

But mocking Mailer was really just a way of putting down ourselves. Mailer's greatest risk was to presume that writing — and writers — mattered. To argue with him was good sport. To dismiss him was to dismiss literature itself.

Though he believed in reincarnation, we shouldn't count on such luck again. He was a man who saw the world whole and still forgave it.

We have only started to miss him.

Mark Twain

I suppose I am the ten millionth reader to say that Huckleberry Finn is an extraordinary work. Indeed, for all I know, it is a great novel. Flawed, quirky, uneven, not above taking cheap shots and cashing far too many cheques (it is rarely above milking its humour) - all the same, what a book we have here! I had the most curious sense of excitement. After a while, I understood my peculiar frame of attention. The book was so up-to-date!

I was not reading a classic author so much as looking at a new work sent to me in galleys by a publisher. It was as if it had arrived with one of those rare letters that say: "We won't make this claim often, but do think we have an extraordinary first novel to send out."

So it was like reading From Here to Eternity in galleys, back in 1950, or Lie Down in Darkness, Catch-22, or The World According to Garp (which reads like a fabulous first novel). You kept being alternately delighted, surprised, annoyed, competitive, critical, and, finally, excited. A new writer had moved on to the block. He could be a potential friend or enemy, but he most certainly was talented.

Ernest Hemingway

Hemingway's style affected whole generations of us, the way a roomful of men are affected when a beautiful woman walks through - their night is turned for better or for worse. His style had the ability to hit young writers in the gut, and they weren't the same after that.

I guess I would say that he occupies the very centre of American writing. No matter how serious or superficial a reader you are, you quickly sense that you are in the hands of someone who writes so well that your wits are keyed afterward to the flaws in the bad writing of others, and, worse, in yourself.

Henry Miller

It is close to incomprehensible that a man whose literary career has been with us over 40 years, an author who wrote one novel that may yet be considered equal to the best of Hemingway, and probably produced more than Thomas Wolfe day by day, and was better word for word, and purple passage for purple passage, a writer finally like a phenomenon, has somehow, with every large acceptance, and every respect, been nonetheless ignored and near to discarded.

We must assume there was something indigestible about Miller that went beyond his ideas. His condemnations are virtually comfortable to us today, yet he is not an author whose complexities are in harmony with our own. Hemingway and Fitzgerald may each have been outrageous pieces of psychic work, yet their personalities haunt us. Faulkner inspires our reverence and Wolfe our tenderest thoughts for literary genius. They are good to the memories we keep of our reading of them - they live with the security of old films. But Miller does not.

He is a force, a value, a literary sage, and yet in the most peculiar sense he does not become more compatible with time - he is no better beloved today than 20, 30, or 40 years ago - it is as if he is almost not an American author; yet nobody could be more American. So he evades our sense of classification. He does not become a personality; rather he maintains himself as an enigma.

DH Lawrence

He was perhaps a great writer, certainly full of faults, and abominably pedestrian in his language when the ducts of experience burned dry, he was unendurably didactic then, he was a pill, and at his worst a humourless nag; he is pathetic in all those places he suggests that men should follow the will of a stronger man, a purer man, a man conceivably not unlike himself, for one senses in his petulance and in the spoiled airs of his impatient disdain at what he could not intellectually dominate that he was a momma's boy, spoiled rotten, and could not have commanded two infantrymen to follow him, yet he was still a great writer, for he contained a cauldron of boiling opposites - he was on the one hand a Hitler in a teapot, on the other he was the blessed breast of tender love, he knew what it was to love a woman from her hair to her toes, he lived with all the sensibility of a female burning with tender love - and these incompatibles, enough to break a less extraordinary man, were squared in their difficulty by the fact that he had intellectual ambition sufficient to desire the overthrow of European civilisation.

James Jones

James Jones and I used to feel in the early 1950s that we were the two best writers around. Unspoken was the feeling that there was room for only one of us. I remember that Jones inscribed my copy of From Here to Eternity "For Norman, my dearest enemy, my most feared friend."

Truman Capote

Capote wrote the sentences of anyone of our generation. He had a lovely ear. He did not have a good mind. I don't know if a large idea ever bothered him.

While he wrote poetically, he did not think like a poet. But he did have a sense of time and place. Breakfast at Tiffany's, for example, is a slight book. Looking at it with a hard eye, it's a charlotte russe. On the other hand, if you are looking to capture a particular period in the 1950s New York, no other book may have done it so well. In that sense, Capote is a bit like Fitzgerald. If I were to mount them on one wall, however, I'd certainly put Truman under Scott.

All the same, Truman Capote was wonderful when all was said. I think of that tiny man who lived through his early years with the public laughing at him. To go from being a pampered little darling with a few friends who catered to him egregiously on to mustering the balls, the enormous balls, to decide he was going to be a major figure in American life - that was his achievement. To hell with writing. He was going to give up writing in order to be a major social figure, and in doing this, I think he sacrificed the last 10 or 20 years of his talent.

Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut and I are friendly with one another but wary. There was a period when we used to go out together fairly often because our wives liked each other, and Kurt and I would sit there like bookends. We would be terribly careful with one another; we both knew the huge cost of a literary feud, so we certainly didn't want to argue.

On the other hand, neither of us would be caught dead saying to the other, "Gee, I liked your last book," and then be met with silence because the party of the second part could not reciprocate. So we would talk about anything else - we would talk about Las Vegas or the Galapagos Islands. We only had one literary conversation and that was over an evening in New York. Kurt looked up and sighed: "Well, I finished my novel today and it like to killed me." When Kurt is feeling heartfelt, he tends to speak in an old Indiana accent.

His wife said, "Oh, Kurt, you always say that whenever you finish a book," and he replied, "Well, whenever I finish a book I do say it, and it is always true, and it gets more true, and this last one like to killed me more than any."

Jonathan Franzen

The Corrections is very good as a novel, very good indeed, and yet most unpleasant now that it sits in memory, as if one has been wearing the same clothes for too many days. Franzen writes superbly well sentence for sentence, and yet one is not happy with the achievement.

It is too full of language, even as the nouveaux riches are too full of money. He is exceptionally intelligent, but like a polymath, he lives much of the time in Wonkville Hollow, for Franzen is an intellectual dredging machine. Everything of novelistic use to him that came up on the Internet seems to have bypassed the higher reaches of his imagination - it is as if he offers us more human experience than he has literally mastered, and this is obvious when we come upon his set pieces on gourmet restaurants or giant cruise ships or modern Lithuania in disarray. Such sections read like first-rate magazine pieces, but no better - they stick to the surface.

He may well have the highest IQ of any American novelist writing today, but unhappily, he rewards us with more work than exhilaration, since rare is any page in The Corrections that could not be five to 10 lines shorter.

Norman Mailer Books

THE NAKED AND THE DEAD

Hailed as one of the finest novels to come out of the Second World War, The Naked and the Dead received unprecedented critical acclaim upon its publication and has since enjoyed a long and well-deserved tenure in the American canon.This fiftieth anniversary edition features a new introduction created especially for the occasion by Norman Mailer.Written in fascinating detail, the story follows a platoon of foot soldiers who are fighting for the possession of the Japanese-held island of Anopopei.Composed in 1948 with the wisdom of a man twice Mailer's age and the raw courage of the young man he was, The Naked and the Dead is representative of the best in twentieth-century American writing.

Click here to buy The Naked and the Dead

WHY ARE WE IN VIETNAM?

When Why Are We in Vietnam? was published in 1967, almost twenty years after The Naked and the Dead, the critical response was ecstatic. The novel fully confirmed Mailer's stature as one of the most important figures in contemporary American literature. Now, a new edition of this exceptional work serves as further affirmation of its timeless quality.Narrated by Ranald ("D.J.") Jethroe, Texas's most precocious teenager, on the eve of his departure to fight in Vietnam, this story of a hunting trip in Alaska is both brilliantly entertaining and profoundly thoughtful.